The content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License.

Reviewed Article:

Adventures in Woad: Woad Dyeing in the Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Worlds

In this article, we explored woad and its uses as a dye on both cloth and skin. Using experimental methods, we constructed woad vats using recipes and techniques from modern, early modern, and medieval times to better understand how dyeing with this key dye material of the ancient and medieval worlds functioned. We also experimented with dyeing techniques on skin to better understand the passage in Caesar's Gallic War which references Gauls with blue-dyed skin. Through our experimentation and the instrumental aid of natural dye expert Maddy Bartsch, we gained a greater appreciation for the technicalities of woad dyeing, demonstrating the ways in which any type of dyeing with woad would have required a great deal of knowledge and acquired skill. We also gained technical knowledge of the various steps of dyeing with fermented woad which helped to illuminate the meaning behind references to these processes in medieval texts. While we could not find a process for dyeing skin blue with woad that would not have rubbed off easily in a battle, we were able to create a variety of vivid colours which expanded our ideas of the medieval colour palette.

Introduction

Woad, a small leafy green plant (See Figure 1), was likely the first blue dye to be in widespread use in Northern Europe, with archaeological and written sources indicating its use from the Bronze Age through the Roman era and into the Medieval period. Our project used experimental methods to explore the use of fresh woad leaves, prepared using both medieval and modern recipes, as a fibre and skin dye. Over six weeks from early August to mid-September 2024, we worked with Theresa Bentz at Get Bentz Farm and Maddy Bartsch at Salt of the North Dye Garden in Northfield, Minnesota to conduct our experiments and to learn more about both the processes of fibre production and natural dyes.

Condensed History of Woad

We first see Woad in the historical record as a skin dye, clothing dye, and medicine. Perhaps the most famous reference to woad in the ancient world comes from Caesar's Gallic War, referring to his 54 BC campaign, in which he describes how "all the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue colour, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible" (Caesar, Gallic War, 5.14). Other ancient authors corroborate the use of woad as a skin dye by the Britons (for example, Pomponius Mela, Description of the World, 3.15 and Pliny, Natural History, 22.2). We also see woad being used for textile dying in Iron Age Scandinavia (Jørgensen, 2003, p.94) and specified as a replacement for indigo in fabric dyeing in the Roman world (Vitruvius, On Architecture II, 7.14.2; Pliny, Natural History, 35.27; Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 2-215). Medical authors praise woad's healing powers, and Hippocrates particularly favoured woad as a kind of "cure all" (Hippocrates, Ulcers, 11; Epidemics 4; Diseases of Woman II, 66; Affections, 38).

Considering its use in the Middle Ages, it is commonly accepted that woad was used as the primary source of blue for textiles in Europe. Early modern sources detail the complex process of fermentation that was used to extract the blue colour from woad leaves (Rosetti, 1969). Woad stayed the most widely used blue textile dye in Europe until the introduction of indigo in the Early Modern period through colonialism and trade, though woad was still used in indigo vats as a "fermenting agent" (Balfour-Paul, 1998, p. 41-2; 57). Indigo was considered more desirable due to its higher concentration of indigens, the chemical that makes things blue in both woad and indigo, as well as its efficacy on cotton fabrics, which were becoming popular in Europe through the 17th and 18th centuries (Munro, 2003, p. 211; Chassagne, 2003, p. 515; Hurry, 1973, p. 293).

Starting from the 18th century, the indigo plant was the major source of blue colours until the introduction of acid dyes in the 19th century. Indigo and woad are similar in appearance and have a similar chemical structure, which creates a blue colour when broken down through fermentation or other chemical processes (Blackburn, Bechthold and John, 2009, p. 194-6). However, notably for the people of the Early Modern era, the concentration of blue-creating chemicals is higher in the leaves of the indigo plant than they are in woad (Balfour-Paul, 1998, p. 2). Acid dyes differ from both of these methods because, rather than being plant-based, these dyes are synthesized from substances such as coal tar (Holme, 2006, p. 235). Despite the use of the indigo plant, various efforts to maintain or revive woad dyeing did exist, often driven by state interests. For example, Napoleon attempted to revive a domestic woad dyeing industry in France to replace indigo, an imported good (Balfour-Paul, 1998, p. 58; Prance and Nesbitt, 2005, p. 303), and woad cultivation continued in England into the early 20th century for use as a fermenting agent in indigo vats used to dye the uniforms of the London police and other servants of the crown (Hurry, 1973, p. 93 and p. 213).

In recent years, attempts have been made to revive woad as a more ecologically responsible alternative to acid dyes. Ian Howard's efforts at the Woad Centre and Woad-Inc demonstrate an interest in producing woad on a large scale, however issues persist due to the great quantity of woad needed for dyeing and the difficulty of producing a blue colour (Howard, 2019). On a smaller scale, a variety of experimental archaeology projects, most notably John Edmund's The History of Woad and the Medieval Woad Vat, have looked at the logistics of woad dyeing and resultant colours (Cardon, Koren, and Sumi, 2023; Hartl, et al., 2015; Padden et al., 2000).

Fibre Trial and Error

Modern Methods

To better understand what cloth successfully dyed with woad looks like, we began from a recipe found with similar variations in Grierson's 1998 The Colour Cauldron, and Foy Cameron's 1998 Woad Zine, that involved steeping fresh woad leaves, and then straining, aerating, and heating the remaining liquid before dying.

There was a great deal of trial and error involved in our process of using modern woad dyeing methods to get the best blue colour possible. One significant finding was that the hardness of the water greatly affects this process. The well on the farm had quite hard water, and when we switched to filtered water, we got darker blues more consistently. This is consistent with period sources that suggest that rainwater was preferable for dyeing. An early modern dye manual, The Plictho of Gioanventura Rosetti, advises the dyer to use "river water or else with rainwater which waters are the best among all others" (Rosetti, 1969, p. 93). After dyeing, we also found that dipping the fully oxygenated yarn in salt water was very effective for getting rid of any lingering green sections (Foy Cameron, 1998, p. 32).

Two benefits of this recipe are that it can scale up or down easily, depending on how much woad you have on hand, and that it does not require fermentation - a long and smelly process. In our experiments, a surprisingly large quantity of woad was required for even a small amount of dye. Additionally, this recipe also requires fresh woad leaves, which highlights the seasonal limitations of working with fresh woad, as its leaves are only usable for dyeing in the summer months (Hurry, 1973, p. 13).

The key differences between this modern recipe and medieval methods is that this version uses fresh woad leaves, rather than fermented, and that it replaces the fermentation process with chemicals, specifically Calcium Oxide and Thiourea Dioxide, to release the indigo pigment (Blackburn et al, 2009, p.195; Grierson, 1998, p.208-9; Foy Cameron, 1998, p.23-32).1 Using chemicals instead of fermentation speeds up the process dramatically so that it can be completed in a day rather than in weeks to months (Christie, 2001, p. 75).

Successful Modern Recipe

We found that a combination of Grierson and Foy Cameron's (Grierson, 1998, p. 208-9) (Foy Cameron, 1998, p. 23-32) methods, with some limited modifications, resulted in our most successful modern recipe for a woad fabric dye:

- Combine about 200 grams of fresh woad leaves (approximately a 2:1 ratio by weight to what you want to dye) with 2 litres of not-quite-boiling water in a jar.

- Leave this jar in the sun for about a half hour and allow the leaves to "steep".

- Once it has steeped, strain off the liquid and squeeze out as much liquid as you can from the leaves using a piece of butter cloth.

- Add about 2 tablespoons of Calcium Oxide (CALX)

- The next step is to aerate the liquid. The most effective way of doing this is to pour the liquid back and forth between two 5-gallon buckets for 5-10 minutes.

- Transfer the liquid into a pot and heat to 120F (50C) and then pour it back into a tall, narrow, bucket for dipping, and add 1 tablespoon of Thiourea Dioxide (formamidine sulfinic acid).

- Let this sit for 30-40 minutes, and the liquid is now ready for dyeing.

- Dip pre-wetted yarn into the vat, trying to introduce as little oxygen as possible, and leave it in for about 5 minutes. Alternate 5 minutes in the vat and 10 minutes out for oxygenation until the desired colour is achieved, keeping in mind that wet yarn is darker than the dried colour would be. Be sure to remove the yarn carefully and to avoid allowing it to drip back into the vat as that introduces oxygen. Oxygenation is an important part of how indigo and woad's pigments work as a dye. Introducing oxygen to the vat can oxygenate the pigment in the vat, rather than on the yarn, and can ruin the vat's ability to create a blue colour.

The 10-minute periods of oxygenation are when the magic happens, and the yarn turns from green to blue (See Figure 2).

Our experiments with modern woad dyeing processes gave us useful insight into working with woad, but they did not provide an authentic experience of working with woad in the medieval period, as we used chemicals that are not found in medieval dye recipes. This led us to question whether the colour derived from woad would be the same when using medieval methodologies and to experiment with medieval techniques.

Medieval Method

To attempt to make a historically accurate recipe for a medieval woad vat, we compiled medieval recipes and methods, early modern dye manuals, secondary literature on medieval woad processes, and more recent studies recorded in John Edmond's The History of Woad and the Medieval Woad Vat (Haigh, 1800; Partridge, 1823; Bemiss, 1815; Rosetti, 1969; Edmonds, 1998; Munro, 1994). There were slight variances in proportions and steps across these sources, but they all followed essentially the same methods: the formation and drying of woad balls, then the rewetting and fermentation of the same woad balls, typically done on a large scale in a purpose-made building, often called a woad floor, and finally the construction of the dye vat.

Our first challenge was making the woad balls. Sources indicate that the woad balls were 2-6 inches in diameter of fresh woad that would take weeks to months to dry entirely (Hurry, 1973, p.24). Due to the time constraints of our experiments, we elected to scale down the size of the woad balls so they would dry more quickly. We picked fresh woad leaves, ripped and mashed them, and then formed them into ping-pong ball sized balls, before squeezing them with butter cloth to remove as much liquid as possible (See Figure 3). Our first round of creating these woad balls resulted in 4 balls weighing 4.0 grams, 3.4 grams, 3.5 grams, and 5.4 grams. We then set these out to dry on drying racks under a fan (See Figure 4). When these woad balls were finished drying, they appeared to have significantly shrunk, and their weight had reduced from a total of 16.3 grams to 14.5 grams. The dried woad balls already appeared to have a bluer tinge to them than before and a stronger smell. The balls were difficult to crush to start the fermentation process, and we utilized scissors to help us break them up. We hypothesized that this was likely due to the balls not being as completely dry as we initially thought. As a result, for our subsequent batches of similarly sized balls we used a food dehydrator. While woad, like many leaves, will naturally dry out if left in a well-ventilated area, full dehydration takes longer than the time that we had for our experiment (Hurry, 1973, p.25). Using a dehydrator is not a historical method, however these machines are commonly used for modern natural dyeing and do not notably alter the results of this process. We found that the balls that had been dried in the dehydrators were easier to crush. As a control, we also dried woad leaves not in balls to crushed them similarly to determine the advantages of removing liquid at an early stage and putting the woad into woad balls.

After crushing the woad balls, the next step is to rewet them to begin the fermentation process. In the medieval period, woad was fermented on woad floors, which Francis Darwin (1896, p.36) described as "the floor of another roofed shed, where [the woad] is sprinkled with water and allowed to ferment" and "the fermenting mass is constantly turned over by the workmen" when he visited the last operating woad mill in England in 1896. This account is similar to the methods discussed in the medieval and early modern periods (Rosetti, 1969, p.92) (Hurry, 1973, p.26). To cover a floor with this much woad, you would need to have a very significant amount of fresh woad, emphasizing that this process occurred on a large scale.

In our experiments, since we were operating with a smaller amount of woad, we wet the crushed woad balls in old yogurt containers covered with butter cloth. This set up was our attempt to replicate the environment of a woad floor on a smaller scale; the lightly covered container served similar purpose as a shed in that it kept the fermenting woad contained, trapped the heat created from decomposition, and kept it from being disturbed by large pests. Having multiple containers also allowed us to have a few different attempts fermenting at the same time. We placed the labelled yogurt containers outside in a warm corner of the garden (See Figure 5). We then rewet and turned the woad in the containers every day we were at the farm, as woad on woad floors would get rewet and turned regularly. We fermented the woad balls for fifteen days before attempting to construct our first medieval vats (See Figure 6).

Our first attempts at medieval vats were constructed based on the methods detailed in Hurry's The Woad Plant and its Dye, which are based on the 1536 De Natura Stirpium along with a variety of Early Modern sources and observations from the last operational woad mill in Britain (Hurry, 1973, p.26 and p. 34). We could not access any earlier detailed recipes, so we decided to base our initial attempt to go off of his description of the 1536 account (Hurry, 1973, p. 34). Hurry's description lacked specific measurements, so we also used the Cambridge History of Western Textiles and woad.org to aid in determining approximate ingredient quantities (Munro, 2003, p. 211; woad.org.uk, 2024). This recipe required boiling madder and bran together in water until the liquid turned a light pink, then adding soda ash, and finally fermented woad. We created two vats with this recipe: one used our first set of woad balls and the other used woad leaves that were dried without being turned into woad balls and fermented for the same amount of time (See Figure 7). We then let the vats sit for three days. When we left them to sit, they were a dark maroon colour and seemed to be promising. However, these vats did work well for us (See Figures 8 and 9). The vat made with woad balls initially turned the yarn green, but the colour did not oxidize and rinsed out quickly, while the vat made with dried leaves did not alter the colour of the yarn at all. However, we hypothesize that the vat made with woad balls might have worked had the woad been better prepared. We particularly surmise that the balls were not dried entirely nor fermented for long enough. Literary sources indicate that the woad should be fermented for nine weeks (Hurry, 1973, p. 26), but we were constrained by the timeline of our time at the farm.

This experiment did however provide valuable information. It indicates that woad balls were an essential step to the success of these medieval vats, as this was the difference between no change in the colour of the yarn and a change towards the desired colour, despite its temporary nature. It also suggests that the medieval method could work and be replicable.

Successful Medieval Trial

Since we did not get a blue colour out of our first vat we decided to try again, this time following John Edmonds' recipe and controlling the temperature and pH of our vat more closely. (Edmonds, 1998, p. 23-8). The recipe that we found most effective, modified from Edmonds', is as follows:

- Gather fresh woad, at least 200-250 grams

- Cut and mash woad up into small pieces

- Form into balls roughly 1-1.5 inch in diameter

- Used a butter cloth to squeeze as much liquid out as possible

- Place balls in a warm, well-ventilated area to dry until completely dried (for a non-period method you could also use a dehydrator in the interest of time)

- Break up dried woad balls, dampen them, then place in a warm area to ferment for at least 2-3 weeks, re-wetting and rotating daily

- When the fermented woad mixture has become smooth and less clumpy allow it to dry fully

- Grind up fermented woad

- In a 2-litre jar mix 1.5 litres of boiling water and soda ash until the pH is 9, using pH test strips to check

- Add the woad and wait for the temperature to go down to 50 degrees C then keep it at 50 degrees C for 30 hours. To maintain temperature, we placed our woad vat in a warm water bath in a large, tall pot with a lid with an aquarium heater. While not a medieval technique, this was intended to imitate round-the-clock attendance of woad vats over fires to maintain temperature (Haigh, 1800, p.23-5).

- After 30 hours dip yarn into the vat and hold it under the surface for 5 minutes.

Our yarn sample turned green and then oxidized to a deep blue colour, meaning that this vat was a success! (See Figure 10)

This experiment showed us the importance of carefully observing pH, temperature, and time in making the woad vat. To do this, we used test strips, thermometers, and accurate watches, none of which were period accurate. However, our need to use these tools emphasizes the amount of skill that those who worked with woad would have acquired over the years so that they could recognize pH, temperature, and time by sight or touch. In his 1823 A Practical Treatise on dying of wollenn, cotten, and skein silk, William Partridge gives a detailed description about what the woad vat should look like at each step of the process, and one can reasonably assume that medieval dyers could similarly control woad vats by sight or feel (Partridge, 1823, 201-5; see also Edmonds, 1998, p.23-8).

After successfully completing a medieval vat, we looked back at some of our source material that we had consulted to figure out the processes and found that many of these references made more sense to us based on the knowledge that we had acquired through the experimental process. One example that we found particularly interesting was a reference to the various stages of woad fermentation from an 8th century Irish law which stipulates that, in the case of divorce, woad should be divided between the two parties differently dependent on which step of the fermentation process it was in (Cáin Lánamna, 2010, section 1; Kelly, 1997, p.265). In the case of divorce, a wife can claim "a third of woad steeping in vats, half if it is caked" (Cáin Lánamna, 2010, section 1). This law makes it clear that a fermentation and drying process was taking place in 8th century Ireland, and that woad was considered to have different values depending on the stage at which it is at the time of fermentation. Thinking about this law in terms of the steps that we had used to create our own woad vats allowed us to better think about the value and logistics of transferring woad at the various stages of fermentation discussed in the law.

Woad Pink

An advantage of using fresh leaves in a modern vat, as opposed to crushed balls in a medieval vat, was the by-product of spent leaves that were available for use after the liquid had been squeezed out (See Figure 11). These leaves can be used to get a lovely secondary colour, ranging from beige to pink. Although the exact shade was quite hit or miss, we did manage to get a variety of pink colours, including a vibrant salmon-pink on one occasion. This recipe, based on the one in Foy Cameron's zine (Foy Cameron, 1998, p. 33-35), is a more straightforward process than trying to get blue out of woad:

- Add depleted woad leaves into a large pot together with the fabric you want to dye and cover with water

- Bring water to a boil.

- Let the fabric sit in the pot with the leaves for 30 minutes, keeping it at a boil. We found this to be an effective length of time to achieve a dark pink colour. Leaving the yarn for longer can ruin the colour.

- Remove and rinse the yarn. The yarn will get pinker as it dries.

We found that this method works very well on wool (See Figure 12). However, on cellulose fibres it turns out a tan colour at best. While spent leaves would not have been a byproduct that was available to dyers using fermented woad balls, this colour could also be achieved by fermenting fresh leaves on a smaller scale. We found that leaving leaves in water in a warm environment for 2-3 days left them exhausted enough to be useable for a spent leaves vat. While we did not find references to a pink colour derived from woad in the dyeing treatises we consulted, there is nevertheless the possibility that the pink colour from woad may have been more accessible for dyeing on a smaller, home scale. Since woad could be winter food source for livestock, woad leaves may have been accessible to a more general population and extracting a pink colour would have required less technical knowledge and fewer additional ingredients than the blue colour (Gent, 1675, p.41-43).

Other Dyes and Colours

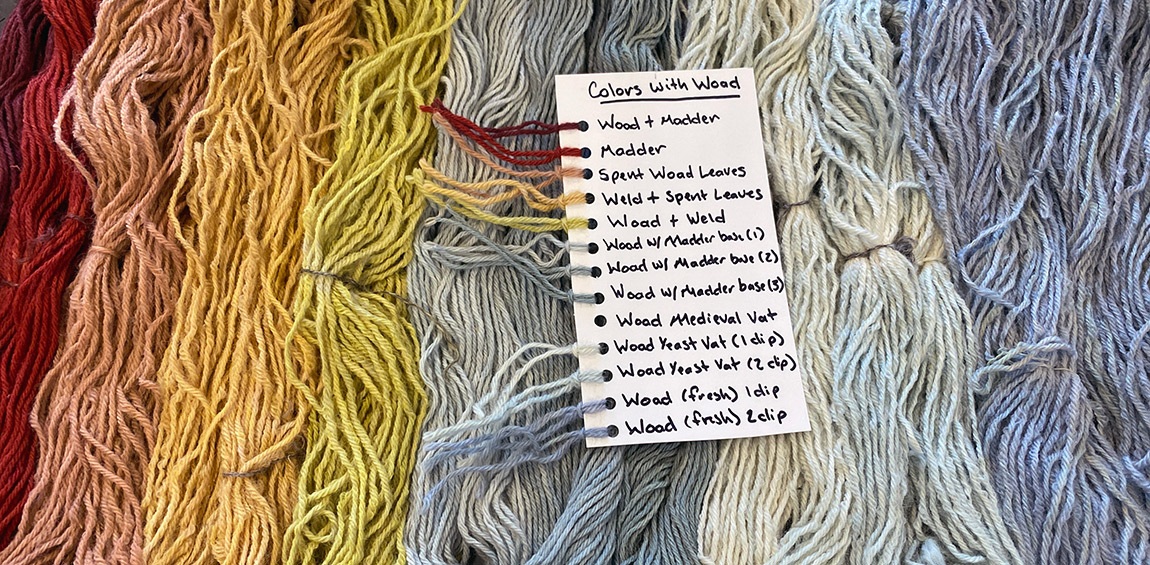

While we mainly focused on woad, we were also interested in working with other natural dyes to build out a "medieval colour palette" of Northern Europe, as well as to gain a point of comparison for dyeing with woad. For this, we focused on madder and weld, which together with woad were the most common sources of primary colours in medieval Northern Europe (Owen-Crocker, 2021, 102) see (See Figures 13 and 14). For instance, there is evidence of both woad and madder being two of the three primary dye sources used in the Bayeux tapestry (Owen-Crocker, 2021, 103). Weld is a plant which gives a bright yellow colour, while madder is a root that gives a deep red (See Figures 15 and 16). We found working with weld the most straightforward of any of the dyes that we worked with as it involved a simple boiling and steeping process, resulting in a very vibrant, sunny, yellow.

We ended up following a recipe, with limited alterations, by Maddy Bartsch as we did not have a period recipe for weld:

- Combine an amount of fresh weld equal to the weight of the yarn that you intend to dye (we used 82 grams) with 12 quarts of water heated to 70 degrees Celsius for 2.5 hours.

- Add a couple of tablespoons of chalk because unlike woad, weld works best with hard water.

- Let the mixture sit overnight

- Strain the plant matter out

- Add pre-wetted yarn and heat the liquid to 70 degrees C

- Remove from the heat and let sit for at least 2 hours

- Remove yarn from liquid and gently rinse out any remaining debris

Madder was slightly more complicated, though still required significantly less effort than woad.

For this we also followed a recipe from Bartsch's recipe with a few minor alterations:

- Clean the roots, stripping them of their outer "bark,"

- Break them up with a mortar and pestle

- Boil the roots, and then let them steep overnight to soften them

- Soak fibre in an alum mordant bath

- Strain the madder out of liquid

- Add pre-wetted, mordanted yarn and bring liquid up to 32 degrees Celsius, then up to 82 C

- Keep the liquid at 82 C degrees for 40 minutes to an hour

- Remove from heat and let sit overnight

- Remove yarn from liquid and gently rinse out any remaining debris

Using woad, weld, and madder allowed us to experiment with the wide range of colours that one could achieve with just these three plants. There is evidence, for example, that medieval dyers would add madder to their woad vats to deepen the colour and perhaps aid in the chemical reduction process (Munro, 1994, p.23; Blackburn, Bechtold, and John, 2009, p.197). We also experimented with layering dyes to get different colours such as greens and purples. Some of these colours, particularly a green we made by overdying a light blue with weld yellow (See Figure 17), were extremely vibrant and a colour that we would usually associate more with an artificial dye. We found the spent woad leaves methods to be somewhat variable and difficult to get any two batches to turn out the same, however, the pinks that we were able to get ranged from beige to a bright salmon. This was, again, a colour that we would not have associated with natural dyes and shows the variety and depth of colours that are possible with natural dyeing techniques. (See Figures 18 and 19)

Skin Trial and Error

A key reference to woad in the ancient world where Julius Caesar says that the Britons used woad to make their skin blue to make their appearance more horrible in battle (Caesar, De Bello Gallico 5.14). This means that people were dying their skin blue and wearing this blue appearance into battle, which indicates that it was visible by their enemies across the battlefield (for Caesar to have seen it) and that it did not immediately come off in battle. Throughout our experimentation with dyeing textiles with woad, we also considered how our techniques of extracting colour from the woad plant may have contributed to how these people may have dyed themselves blue with woad.

There have been a number of theories about how woad may have been used to colour skin, including by rubbing crushed woad on the body, suspending pigment extracted from woad in a fat and using the mixture to paint the body, and creating an ink with the woad that is then tattooed into the skin. Since scholars do not agree how people used woad to colour skin, we hoped an experimental approach might shed light on the issue.

We first tried rubbing the crushed woad on our bodies to stain them blue. Through both the crushing and manipulation of the woad with our hands and then rubbing this on our arms we were able to stain our skin. However, this stain was a darker and duller grassy green rather than a bright green or a shade of blue. Additionally, this stain came off easily, even after letting it dry, and the addition of a little water or sweat made its removal even easier. We doubt that this method of staining skin would have worked as it was not blue and it was easily removed such that it would not survive if the wearer was sweating, such as if they were in battle. We later also, with our modern vat, found that the bubbles formed were a bright blue colour and if we allowed them to dry on our skin then our skin would be dyed a similar bright blue colour (See Figure 20). This stain was similarly easily removable.

Our next attempt was to create a pigment that could be either suspended in a fat for use as a body paint or used to create tattoo ink. Since a powdered pigment can be extracted from indigo, we were hopeful it could be extracted from woad as well. There is some evidence that a skimming technique was used in the medieval era to make blue paint from this byproduct of woad vats (Kirby, 2021, p.48), so we tried taking the blue bubbles from the modern dye vat, allowing them to dry, and then collecting the resulting powder. This created a deep and bright blue colour but was derived from modern rather than medieval methods. Additionally, the amount of powder that we got from this technique was very limited, and while a larger vat would have created more powder, we wanted to see if there was a way that we could just make the powder itself.

We also tried a method used to extract pigment from indigo. We filled a 5-gallon bucket with woad leaves then added water to cover the leaves. We left this outside for two days in the hot August weather (30 degrees Celsius) to ferment. We then removed the woad leaves, using butter cloth to squeeze all of the liquid out of the leaves, and then strained the whole liquid through butter cloth to get the rest of the chunks out. We then added 5 tablespoons of pickling lime and aerated the mixture by pouring it back and forth between 5 gallon buckets a handful of times. This method was unsuccessful, and we could not get a blue colour.

We attempted the process again when the weather was cooler (25 degrees Celsius), substituted pickling lime for Calcium Oxide, an ingredient also found in Roman concrete sometimes known as quicklime (Seymour et al., 2023), and increased the aeration time to 30 minutes and did get a blue colour. After aeration we decanted the liquid into large jars and let it sit overnight to let the pigment settle to the bottom. The next day we removed the liquid off the top so that we were left with just the pigment. This is a painstaking process with a straw so that it does not disturb the pigment and cause it to mix back into the rest of the liquid. We then spread the pigment over coffee filters suspended over jars to let the pigment to dry into a powder (See Figure 21). From this initial 5-gallon bucket full of fresh woad, we got a quite small amount of pigment that was more of a blue-green colour than a dark blue (See Figure 22). Like many other methods of dyeing with woad, this method required a great deal of woad and effort for a small amount of pigment but was relatively effective.

We attempted three different methods to apply these two powders to our skin. First, we applied the powder from the indigo-method directly to our skin. This would have been achievable historically but resulted in very little colour on our skin and the colour that was present was a very muddy blueish green colour. The powder retrieved from the bubbles on the modern vat was a slightly bluer colour but was not notably blue from even one meter away. This powder came from a process that was not directly replicable in the ancient world because Thiourea Dioxide is a modern chemical. However, the Thiourea Dioxide is being used in place of the fermentation process. Similar bubbles could be created through aerating dye vats that were fermented over a longer period, such as with the medieval methods. The effect of these powders on the skin was reminiscent of a minor bruise. Additionally, both powders brushed off very easily. We concluded that applying powdered woad in this manner would not have been visible let alone notable from across a battlefield and it would not have survived anything or anyone touching it.

Second, we suspended the powder in a fat to attempt to create a mixture that would better bond the colour to our skin. We mixed beef tallow with the two different woad powders, mixing powder into the tallow until we felt like we had created approximately the same colour as the powder itself, which used a significant amount of powder. Much like the powder on its own, the tallow/powder mixture applied to the skin looked most reminiscent of a bruise and was not discernible even a meter away. We tried adding more powder to intensify the colour, and while it did become more visible, it still appeared highly bruise-like and was indiscernible from 2-3 meters away. For both mixtures this slight tinge of the skin was easily rubbed off, especially when the body was sweaty. We concluded that powdered woad mixed with tallow was not visible from far away, easily came off with sweat, and was not notably blue or green.

Third, we attempted to make tattoo ink from these powders. A local tattoo artist gave us a recipe they used to create tattoo ink from ash, and we replaced ash with woad powder: 90% witch hazel, 5% food-grade alcohol (Everclear), 5% glycerine, and the powder (not counted in percentages). Not all of these ingredients would have been available in the ancient world, and this recipe is based on a modern method. Given the potential risks of injecting plant matter into the body, including skin infection and other more serious conditions, we decided to prioritize safety. Despite the modern ingredients, this method isolated woad pigment as the only variable, since we know the recipe works with other natural pigments such as ash and allowed us to see if this woad pigment could be suspended in tattoo ink and applied to skin.

We mixed these ingredients together leaning towards a thicker mixture that carried the blue colour of the powder. Barsch used the ink to give Banta a small stick and poke tattoo near their left ankle. Initially, this experiment proved highly exciting, as the ink was visible in the skin and it was a blue colour! Because the tattoo was small it was difficult to see from a distance, but the colour was such that a bolder tattoo would be more visible. However, the tattoo faded leaving just a colourless scar after a month.

Conclusions

The experimental method has allowed us to better understand woad and greatly clarified how we view woad when we read about it in ancient and medieval sources. The long process that it took to make a blue colour, on clothing or skin, has emphasized to us the amount of knowledge and skill that would have been required for dyeing with woad. Particularly in the case of skin dyeing, our inability to find an immediately viable option for dyeing skin with woad points to a deep set of cultural knowledge about dyeing with woad. Even with the aid of more modern materials and processes, we could not create a woad-based skin dye or tattoo ink that would have been viable for use in high-impact physical situations. The creation of this dye most likely took a great deal of time and preparation raises a whole other set of questions about the cultural, and potentially religious, significance of not only the blue colour, but also the process of creating and applying a kind of pigment for the skin that would remain intact in extreme circumstances.

Turning to the case of fibre, the amount of woad that it took to dye even a small amount of woollen yarn suggests to us the scale at which woad must have been produced and processed to support a woollen textile trade. It also made clear to us why indigo, which makes a more highly concentrated dye, would have been appealing when it became available to a European market (Balfour-Paul, 1998, p.54). We found that woad works best on wool, rather than cellulose fabrics like cotton, which also supports secondary sources which discuss the growing demand for dyed cottons in Europe in the 18th century as a possible driving factor behind the switch to indigo in this period (Chassagne, 2003, p.515). The medieval vat is another place in which the skill involved in this process was emphasized to us, as our various rounds of experimentation showed just how tightly factors needed to be controlled for a successful vat to occur.

Additionally, the variety of colours that we were able to get out of woad leaves themselves, particularly the deep pink that we achieved from the spent leaves and the colours that we got when we mixed the woad with dyes, expanded the idea of a "medieval colour palette" in our minds and questioned the stereotypical idea of medieval life as a drab brown and grey. Some of the colours that we got were quite bright and even iridescent at times and really pushed us to think about what kinds of bright colours may have been accessible to medieval people, particularly those who had the means to access dyes.

Thinking about woad and the amount of labour and woad required for dyeing, it also suggests that it was blue dye from woad most likely not something that could be achieved easily on a domestic scale. However, the pink secondary dye raises more opportunities. Extracting a pink colour from woad is a relatively straightforward process that could be achieved from fresh leaves and does not require a great number of leaves, and while this would be seasonally dependent, it may have been accessible to a wider group of people. Similarly, weld and its bright yellow, does not require a complex dyeing process aside from boiling. While rich, dark colours were almost definitely still reserved for people of higher classes, examination of dyeing practices raises a possibility that there was a somewhat expansive colour palette available to a wider variety of social classes.

Places for Further Research

While we learned a great deal about woad from our research, there is much more that could be learned given more time and resources. First, the construction of a full-scale woad mill was not something that we had time or resources to achieve but would be essential for getting at the full experience of medieval woad dyeing. Along similar lines, there is still much work to be done investigating a way of making woad more viable for home dyeing on a smaller scale or creating a shelf-stable woad dye product for home dyers who want a more ecologically friendly alternative to acid dyes. Finally, the question of how the Gauls dyed themselves blue remains. There is still much research to be done about how this could have been achieved without the blue colour rubbing off in the stress of battle.

Acknowledgements

We cannot thank Maddy Bartsch and Theresa Bentz enough for providing us a space for our trials and errors, supplying specialized ingredients for natural dyeing, encouraging and enabling us to do the kinds of experiments that we wanted to do, and being so generous with their knowledge. We would also like to thank the Carleton College Humanities Center for financial support, and Jake Morton for support throughout our research and writing process.

- 1

For more information on the chemical processes behind the extraction of colour from woad see Blackburn et al. (2009) The development of indigo reduction methods and pre-reduced indigo products.

Keywords

Bibliography

Balfour-Paul, J., 1998. Indigo. Chicago, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers.

Barnett, E. D. B., 1910. The Action of Hydrogen Dioxide on Thiocarbamides, Journal of the Chemical Society, 97(1), pp. 63-5.

Bemiss, E., 1815. The Dyer's Companion. New York, Duyckinck.

Blackburn, R.S., Bechtold, T. and John, P., 2009. The Development of Indigo Reduction Methods and Pre-Reduced Indigo Products, Colouration Technology, 125(4), pp. 193-207.

Cáin Lánamna, 2010. Translated by Donnchadh Ó Corráin. Cork, Ireland: CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts. < https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T102030.html. >

Cardon, D., Koren, Z. C., and Sumi, H., 2023. Woaded Blue: A Colourful Approach to the Dialectic Between Written Historical Sources, Experimental Archeology, Chromatographic Analyses, and Biochemical Research, Heritage, 6(1), pp. 681-704.

Carr, G., 2005. Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain, Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 24(3), pp. 273-292.

Chassagne, S., 2003. Calico Printing in Europe Before 1780. In D.T. Jenkins, ed. Cambridge History of Western Textiles. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 513-527.

Chenciner, R., 2000. Madder Red: A History of Luxury and Trade: Plant Dyes and Pigments in World Commerce and Art. Richmond, Curzon.

Christie, R. M., 2001. Colour Chemistry. Cambridge, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Darwin, F. and Meldola R., 1896. A Visit to an English Woad Mill, Nature, 55(1411), pp. 36-37.

Edmonds, J., 1998. The History of Woad and the Medieval Woad Vat. Buckinghamshire, Chilton Open Air Museum.

Foy Cameron, N., 1998. Woad: Its History, How to Grow it, How it Works, How to get Colour Out of it. UK, Printed by the author.

Gent, J. W., 1675. Systema Agriculturæ: The Mystery of Husbandry Discovered, 2nd edition. London, Printed by J.C. for T. Dring.

Grierson, S., 1986. The Colour Cauldron. Perth, Mill Books.

Haigh, J., 1800. The Dyer's Assistant in the Art of Dying Wool and Woollen Goods. London, Printed for J. Mawman.

Hambly, W. D., 1925. The History of Tattooing and Its Significant, with Some Account of Other Forms of Corporal Marking. London.

Hartl, A., Proaño Gaibor, A.N., Van Bommel, M., and Hoffman-de Keijzer, R., 2015. Searching for Blue: Experiments with woad fermentation vats and an explanation of the colours through dye analysis, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2, pp. 9-39.

Holme, I., 2006. Sir William Henry Perkin: a review of his life, work and legacy, Coloration Technology, 122(5), pp. 235-299.

Howard, I., 2019. Woad: Field to Fashion. Norfolk, Barnwell Print.

Hurry, J. B., 1973. The Woad Plant and its Dye. Clifton N.J.: A.M. Kelley.

Jørgensen, L. B., 2003. Northern Europe in the Roman Iron Age, 1 BC - AD 400. In D. T.

Jenkins, ed. Cambridge History of Western Textiles. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 93-101.

Kelly, F., 2000. Early Irish Farming: a study mainly on the law-texts of the 7th and 8th centuries AD. Dublin, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Kirby, J., 2021. Technology and Trade. In C. P. Biggam and K. Wolf, eds. A Cultural History of Colour: In the Medieval Age. New York Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 97-112.

Leggett, W. F., 1944. Ancient and Medieval Dyes. New York, Chemical Pub.

Munro, J. H., 2003. Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Technology and Organization. In D.T.

Jenkins, ed. Cambridge History of Western Textiles. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 181-227.

Munro, J. H., 1994. Textile Technology in the Middle Ages. In J.H. Munro, ed. Textiles, Towns and Trade: Essays in the Economic History of Late-Medieval England and the Low Countries. Aldershot, Hampshire, Variorum, pp. 1-27.

Owen-Crocker, G. R., 2021. Body and Clothing. In C. P. Biggam and K. Wolf, eds. A Cultural History of Colour: In the Medieval Age. New York, Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 97-112.

Padden, A. N., John, P., Collins, D. M., and Hall, A.R., 2000. Indigo-reducing Clostridium Isatidis: Isolated from a Variety of Sources, Including a 10th-century Viking Dye Vat, Journal of Archaeological Science 27(10), pp. 953-956.

Partridge, W., 1823. A Practical Treatise on Dying of Woollen, Cotton and Skein Silk, the Manufacturing of Broadcloth and Cassimere. New York, H. Wallis.

Prance, G. T. and Nesbitt, M., 2005. The Cultural History of Plants. New York, Routledge.

Pyatt, F. B., Beaumont, E. H., Lacy, D., Magilton, J. R. and Buckland, P. C., 1991. Non isatis

Sed Vitrum or, the Colour of Lindow Man, Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 10, pp. 61-73.

Roberts, M., 2024. Woad.org.uk. Available at: < https://www.woad.org.uk/index.html. > [Accessed 18 May 2025].

Rosetti, G., 1969. The Plictho of Gioanventura Rosetti. Translated by S.M. Edelstein and H.C. Borghetty. Cambridge, M.I.T. Press.

Rodenki, S. I., 1970. Frozen Tombs of Siberia: the Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. Translated by M. W. Thompson. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Seymour, L.M., Maragh, J., Sabatini, P., Di Tommaso, M., Weaver, J.C. and Masic, A., 2023. Hot Mixing: Mechanical Insights into the Durability of Ancient Roman Concrete, Science Advances, 9(1). doi.org10.1126/sciadv.add1602.

Turner, R. C. and Scaife, R. G., 1995. Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives. London, British Museum Press.

Van Der Vee, M., Hall, A.R. and May, J., 1993. Woad and the Britons Painted Blue, Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 12(3), pp. 367-371.

Classical Sources:

Caesar, J., 1946. The Gallic War. Translated by H.J. Edwards. Loeb Classical Library 72. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Dioscorides, 2000. De Materia Medica. Translated by T. A. Osbaldeston. Johannesburg, Ibidis Press.

Hippocrates, 1988. Affections. Translated by P. Potter. Loeb Classical Library 472. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Hippocrates, 1994. Epidemics 2, 4-7. Translated by W. D. Smith. Loeb Classical Library 477. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Hippocrates, 1995. Places in Man. Glands. Fleshes. Prorrhetic 1-2. Physician. Uses of Liquids.

Ulcers. Haemorrhoids and Fistulas. Translated by P. Potter. Loeb Classical Library 482. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Hippocrates, 2018. Diseases of Women 1-2. Translated by P. Potter. Loeb Classical Library 538. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Pomponius Mela, 1998. Description of the World. Translated by F.E. Romer. Ann Arbor, Michigan, The University of Michigan Press.

Pliny, 1952. Natural History, Books 33-35. Translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 394. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Pliny, 1969. Natural History, Books 20-23. Translated by W. H. S. Jones. Loeb Classical Library 392. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Vitruvius, 1934. On Architecture, Volume II: Books 6-10. Translated by F. Granger. Loeb Classical Library 280. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.