The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

A Missing Link in the Chaîne Opératoire

How elitist attitudes shape archaeological interpretations. A curious misunderstanding arose while writing about Bronze Age metalworking hearths and smiths. I stated that no tools are found at metalworking sites after the work was completed as the tools and materials would have been taken away. The reader took the statement to infer that I was arguing for the idea that metalsmiths were itinerant, as described by Gordon Childe (Childe, 1940, p.176); that they packed up and left for another settlement...

Introduction

... What I meant to express was that once the work was completed for the day, and especially if conducted outdoors, the tools would be taken to where they would be stored and be safe from the elements. It seemed a logical assumption. In all professions, even archaeology, tools and equipment are put away when the day's work is finished, but in studies of chaîne opératoire, there does not appear to be a provision for this. In metallurgical studies the description of the chaîne opératoire moves from the steps necessary to create an object, to its use and eventual deposition. The care and storage of tools, however, is completely ignored.

The links in the Chaîne: Organising technology

Chaîne Opératoire, the operational sequence through which objects are manufactured, was pioneered by anthropologists including Leroi-Gourhan, Lemonnier, and Creswell (in Audouze, 2002, pp.279-81 287, 299), who set out to create a system in which the production processes for the creation of prehistoric stone tools could be organised (Bar-Yosef and Van Peer, 2009, p.104). Others saw the need for a system to study the organisation of technology (Bleed, 2001, pp.101-2; Binford, 1979, pp.255-261). These lines of study aimed to reconstruct the sequential steps used in creating objects in order to understand the technological choices made by people in prehistory (Lemonnier, 1986, p.149). These processes begin with the steps necessary for the initial procurement of raw materials, and continue with their processing, the creation of an object, its use, and eventual 'death' through destruction or deposition (Bleed, 2001, p.102) The system was adopted by other branches of material studies in archaeology, and since then has been a standard tool for understanding manufacturing processes (Renfrew and Bahn, 1996, p.372). In metallurgy, this could include a sequence beginning with mining, preparing ore, and smelting, then proceeding to creating moulds and crucibles, casting, finishing the object, and finally its use, and eventual recycling or destruction.

There are detailed descriptions of the chaîne opératoire of various crafts, but despite this there are gaps. Bar-Yosef and Van Peer (2009, pp.107-113) pointed out some of these shortcomings in their paper where they expressed problems with rigidity in the system, and that while chaîne opératoire provided a taxonomic system for understanding manufacturing processes, it still did little to inform about prehistoric life and practice.

It is possibly because of this rigid approach, in which the concentration is focused on specific tasks, that some parts of the process are missed. The result is that some tasks are not recognised and become 'out-of-sight/out-of-mind'. The situation resembles a motion picture in which commonly assumed activities have been edited out. Unless an activity such as cleaning up is necessary to move the plot along, it is excluded from most narratives. This is also seen in archaeological studies where the clean-up and storage of tools is omitted because this is not seen to have a direct impact on the finished object. In archaeology, however, when we are trying to study human behaviour in the past, these gaps have consequences. We are missing an integral aspect of an activity because we assume it is there, and do not afford it importance because we do not recognise it as such.

Acknowledging the missing links

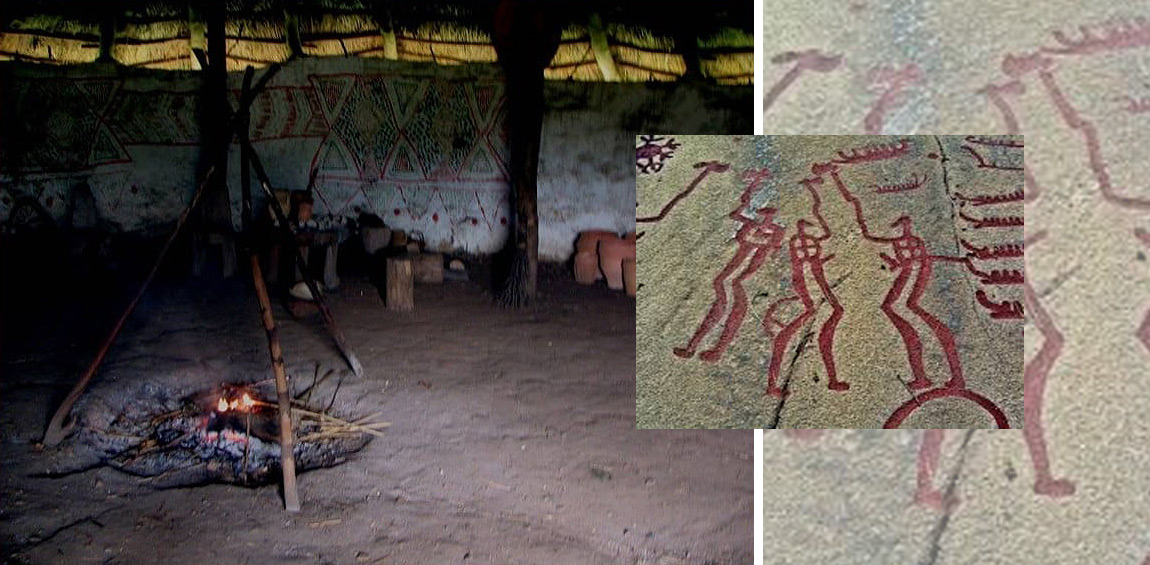

In studying the recreation of Bronze and Iron Age roundhouses, it is apparent that there is a serious lack of interior furnishings. Recreated roundhouses are usually bare except for a hearth and a couple of logs that serve as seats (a presentation about this is available at http://sheffield.academia.edu/...). In these houses, there is very little that connects the houses with the material culture and the activities of people living there. There is no place to put away tools, materials, or even clothing. In mentally reconstructing the chaîne opératoire, these objects are not put away because, in our minds, we have not provided a place to put them. The items that are not needed at that moment become invisible, and the study moves on to what might be considered more important sequences of events. In doing so, we are missing entire categories of activities that should be accounted for if we wish to understand the daily lives of people in prehistory.

An example would be to look at the literature written about copper alloy axes. Much has been written about them, including wear analysis and use-life (Roberts and Ottaway, 2003, pp.124-133; Mathieu, 2002, pp.5-6; Mathieu and Meyer, 2002, pp.74-76; LeMoine, 2002, pp.13-18). The majority of studies focus on the types of damage, and how long tools might be used before they need to be resharpened. The literature, however, is silent on other aspects such as cleaning and storage. The manufacture of all the necessary tools for a workshop represents an investment in time, materials, and labour that cannot not be recovered. This is an even greater concern in pre-industrial societies when it was necessary for all tools to have been crafted by hand. Maintenance will ensure that the tool continues to function properly since the condition will affect not only the tool's performance, but also the quality of the objects produced. Tools that are neglected perform poorly, and they will also point to an artisan who might compromise the quality of finished work. Thus, their care, storage, and maintenance speak to the value of tools and the shared identity of the tools with the craftworker.

Tools and the chaîne of communication

Tools can carry significant symbolic weight. Examples such as the hammer and sickle, the symbol of the former Soviet Union, elicit a variety of reactions from those who lived through the Cold War. Symbols such as these serve as semiotic devices that are loaded with meanings that communicate a message to be interpreted by the observer (Chandler, 2002, p.29). In the Bronze Age, axes appear as graphic symbols. They are carved into the sarsen stones at Stonehenge, they appear in rock art in Valcomonica, and other sites around Europe. The significant locations of these representations demonstrate that these symbols had some importance to the people of the Bronze Age (Roberts and Ottaway, 2003, pp.136-137; Patton, 1989, p.68; Bradle, 1998, pp.9, 83-4).

In a response that was published within the 2009 article by Bar-Yosef and Van Peel, Iain Davidson cited works written in which the actions that constitute the chaîne opératoire could also constitute a syntax (Bar-Yosef and Van Peer, 2009, p.119). Thus the use of tools become a means of enabling communication through the performance of creating objects (Ingold, 1994, pp.432, 438; Wynn, 1994, p.389). They 'mediate an active engagement with the environment' (Ingold ,1994, p.433) and provide a means of understanding the world (Ingold, 1994, p.432; Nikolaidou, 2007, p.184). By ignoring important aspects of the chaîne opératoire such as maintenance, we are missing pieces of information in this sequence of communication.

Chaîne opératoire and forging relationships

Tools also represent the continuance of tradition (Rowlands, 1993). Among Nigerian metalsmiths, in the Igbo rite of passage from apprentice to a full metalsmith, the initiate is given a set of tools, including an ótutù, a hammer that symbolises his new status as smith and the ability to take on his own apprentices (Neaher, 1979, p.358). In conferring the ótutù, the new smith is given a new identity that connects him to traditions that go beyond living memory, and the power to train and initiate others into the tradition. Thus, the working hammer used by the Igbo smiths is not only a tool of their trade, but it is also a symbol of their mastery, and their inherited tradition.

Tools are frequently understood to have a life of their own. This is not simply an animistic belief, but the recognition of tools as instruments that enable the artisan to bring other objects into being.

'…it is the dynamic, transformative potential of the entire field of relations within which beings of all kinds, more or less person-like or thing-like, continually and reciprocally bring one another into existence. The animacy of the lifeworld, in short, is not the result of an infusion of spirit into substance, or of agency into materiality, but is rather ontologically prior to their differentiation'

(Ingold, 2006, p.10).

Over their lifetimes, tools develop characteristic wear. The blades on axes can become distorted and flared with repeated sharpening through hammering and annealing. Tools might also develop a 'side' from repeated use without variation, such as an archaeologist's trowel in which the point is off centre from years of trowelling using only the dominant hand. The wear indicates not only the long use-life of the tool, but also the gradual adaptation of the craftworker to the changes in the tool. This adaptation to their tools creates a unique relationship where the tool is more than a piece of equipment to accomplish a task. It becomes an extension of the mind and body of the artisan (Ingold, 2000, p.440; Brück, 2006, p.75; Nikolaidou, 2007, p.184). This is emphasised when we consider that metalsmiths must use tongs, crucibles, and other tools because they cannot handle the heated metal with their bare hands. The smith must be able to use these tools precisely and accurately in order to create metal objects.

In addition, the performance of craftworking has often been compared to ritual in which a set series of codified acts must be performed to ensure a successful outcome (Gell, 1988, p.9). These sequences are handed down and become fixed in tradition as apprentices watch their masters and learn the successive steps to complete objects. Here the chaîne opératoire becomes linked with ritual (Nikolaidou, 2007, pp.184-185). Pfaffenburger wrote that chaîne opératoire and ritual are inextricably intertwined (Pfaffenburger, 1992,p. 505; Nikolaidou, 2007, pp.184-185) where tools are considered partners in the creative act (Pfaffenburger, 1992, p.505). If we can accept this, then the importance of care and maintenance of tools gains added significance.

Forging a new link in the chaîne

The value of tools equates with valuing ourselves, as both an extension of our bodies (Brück, 2006), and as a means of communicating with the world through performance and the created objects (Ingold, 1994, pp.432, 438; Wynn, 1994, p.389). Tools must be maintained and properly stored for them to continue to function in this capacity.

In modern society the concept of cleaning up after ourselves is considered drudgery. We often tend not to think about it, other than as an obligatory and often disliked part of life. But it is necessary, and it must be done. In a life where there is a dependence on the use and performance of tools, the nit-picking details and obligations of maintenance are important. For this we should consider how tools are maintained, in addition to how and where they are stored. In order to see the full picture of how craft was practiced in the past, we have to include all the tasks in the chaîne opératoire. That includes considering how tools and materials are maintained and stored when the work is completed.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor John C. Barrett, who encouraged me to pursue this idea.

Keywords

Bibliography

Audouze, F., 2002. Leroi-Gourhan, a Philosopher of Technique and Evolution. Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 10, No. 4,

Bar-Yosef, O., and Van Peer, P., 2009. The Chaine Operatoire Approach in Middle Paleolithic archaeology. Current Anthropology 50 (1), pp.103-131.

Binford, L. R., 1979. Organization and formation processes: Looking at curated technologies. Journal of Anthropological Research 35, pp.255-273.

Bleed, P., 2001. Trees or chains, links or branches: Conceptual alternatives for consideration of stone tool production and other sequential activities. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 8, pp.101-127.

Bradley, R., 1998. The Passage of Arms: An archaeological analysis of prehistoric hoard and votive deposits. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Brück, J., 2006. Death, Exchange and reproduction in the British Bronze Age. European Journal of Archaeology 9 (73).

Chandler, D., 2002. Semiotics: The Basics. London, Routledge.

Childe, V.G., 1940. Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles. London, W. & R. Chambers, Ltd.

Gell, A., 1988. Technology and Magic. Anthropology Today 4 (2).

Ingold, T., 1994. Tool-use, sociality and intelligence. In K. R. Gibson and T. Ingold. eds. Tools, Language and Cognition in Human Evolution. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Ingold, T., 2000. Tools, minds and machines: An excursion in the philosophy of technology. In The Perception of the Environment: Essays in livelihood, dwelling and skill. London, Routledge.

Ingold, T., 2006. Rethinking the Animate, Re-Animating Thought. Ethnos 71 (1).

LeMoine, G., 2002. Monitoring Developments: Replicas and Reproducibility. In J. R. Matthieu, ed. Experimental Archaeology: Replicating past objects, behaviors, and processes. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Lemonnier, P., 1986. The Study of Material Culture Today: Toward an

Anthropology of Technical Systems. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 5 5.

Mathieu, J.R., 2002. Introduction. In J. R. Mathieu, ed. Experimental archaeology, replicating past objects, behaviors and processes. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Mathieu, J.R., and Meyer, D.A., 2002. Reconceptualizing Experimental Archaeology: Assessing the Process of Experimentation. In J. R. Mathieu, ed. Experimental archaeology, replicating past objects, behaviors and processes. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Neaher, N., 1979. Awka who travel: Itinerant metalsmiths of Southern Nigeria. Africa 49 (4).

Nikolaidou, M., 2007. Ritualized Technologies in the the Neolithic? The crafts of adornment. In E. Kyriakidis, ed. The Archaeology of Ritual. Los Angeles, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology.

Patton, M.A., 1989. Axes, Men and Women: Symbolic Dimensions of Neolithic Exchange in Armorica (north-west France). In P. Garwood, D. Jennings, R. Skeates and J. Toms, eds. Sacred and Profane: Proceedings of a Conference on Archaeology, Ritual and Religion. Oxford, Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph No. 32.

Pfaffenburger, B., 1992. Social Anthropology of Technology. Annual Review of Anthropology 21.

Renfrew, C. and P. Bahn., 1996. Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice. 2nd ed. London, Thames and Hudson.

Roberts, B., and Ottaway, B.S., 2003. The use and significance of socketed axes during the Late Bronze Age. European Journal of Archaeology 6 (119).

Rowlands, M., 1993. The Role of Memory in the Transmission of Culture. World Archaeology 25 (2), pp.141-151.

Wynn, T., 1994. Layers of thinking in tool behavior. In K. Gibson and T. Ingold, eds. Tools, Language, and Cognition in Human Evolution. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Source for Figure 3: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_Carvings_in_Tanum