The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

The Transformation of Glass Debris from Apollonia-Arsuf (Byzantine Sozousa)

The site of Apollonia-Arsuf (Byzantine Sozousa) is located on the Mediterranean coast, some 17 km north of Jaffa (Joppa) and 34 km south of Caesarea Maritima, Israel. The site has been excavated continuously over the last 40 years by the Apollonia-Arsuf Excavation Project. Once a modest coastal settlement, it became the main urban centre of the southern Sharon plain in Byzantine times (4th-7th centuries AD). It was during that period that the site became a major centre of primary (and secondary) glass production (Freestone, 2020), with several excavated primary glass furnaces and additionally documented ones on its terrain (Tal, Jackson-Tal and Freestone, 2004; Freestone, Jackson-Tal and Tal, 2008; Tal, 2020, pp.60-80 passim).

Introduction

One such primary glass furnace was excavated by the current Apollonia-Arsuf expedition in 2002. Excavation revealed a two-part furnace, built of a mud-brick superstructure over ashlar walls, likely reusing earlier building stones. The firing chamber was divided to two chambers that faced west, using sea winds for airflow and a melting chamber that likely had a vaulted roof with vents on the east. A large raw glass slab (4.45×2.95 m) was discovered partially dismantled.

Reconstructing of the production process can be made by an ethnographic study made in Jalesar in northern India (Torben and Kock, 2001). Although glass furnaces there are circular in plan (external D. about 5 m), they consist of firing and melting chambers and are thus technically comparable to ours. The fuel used at Jalesar was stalks from nearby mustard plants, we assume that in our case wood remains (trunks, branches and twigs) were burned to charcoal, in the nearby Sharon forest as fuel. The ethnographic study showed that it took 30 days and a constant temperature of about 900°C to produce a circular glass slab. This chamber was filled, through an opening in its wall, with about three tons of sand free of organic impurities and stirred periodically. Every third day, about 300 kilograms of batch were added to clumps of poor-quality glass from the previous melt. This enhanced the process, since glass that has already been melted reacts at lower temperatures. An additional two weeks were needed for the glass slab to cool. It was then broken into pieces, but only a little more than half of the raw glass was acceptable for manufacturing.

The glass chunks produced by this process at Apollonia (Sozousa) were blue, greenish blue, yellowish green, and brownish tones in colour. A 6th–7th century CE storage jar fragment, unearthed below its foundations, provided a terminus post quem for its date of construction. Chemical analysis using electron microprobe revealed that that the glass is soda-lime-silica, typical of Late Roman/Byzantine/early Islamic Levantine tank furnaces (Tal, Jackson-Tal and Freestone, 2004). Additional analysis made on the 6th–7th century CE glassmaking industry at Apollonia suggested it was a major producer of raw glass distributed across the Mediterranean, as is evidenced from chemical and isotopic analysis (Freestone, 2020). These analysis show that the Apollonia soda-lime-silica glass was made with Egyptian natron and coastal sands rich in shell-derived calcium carbonate. It is normally light greenish-blue color, not deliberately decolourized, with low levels of contaminants (Fe, Mg, K) and ~3% alumina, inherited from the sand. Strontium and neodymium isotopes link it to Levantine coastal sands ultimately derived from Nile sediments.

Apollonia glass is Distinguishing from other Levantine centers such as Jalame (4th c.) and Bet Eli‘ezer (7th–8th c.) each have overlapping but distinct compositional ranges. Earlier scholarship grouped these under “Levantine I,” but new analyses show they align specifically with Apollonia. It has lower soda than earlier Roman or Egyptian glass, and an absence of manganese is a strong indicator of Apollonia production (Roman and Jalame glass often contain Mn or Sb as decolourants). It also shows that Apollonia glass is the main raw material for 6th–7th century vessels in Israel, and its presence across the Mediterranean is attested to sites in Cyprus and Visigothic Spain, as well as Carthage. Moreover, Apollonia glass is frequently used as a base for opaque colours. Particularly important for greens and turquoise, because its low manganese avoids unwanted pink hues during copper-based coloration. —Apollonia material remained widely used, including as base glass for Byzantine mosaic tesserae.

The abundance of small chunks of raw glass and furnace building material debris across the site’s surface is apparent nowadays to its visitors (See Figure 1a). Furthermore, excavations have repetitively revealed in almost every area of excavation the use of primary-raw glass as building materials embedded in walls of many of the post-Byzantine structures (See Figure 1b). This phenomenon is visible within the perimeter of the fortified medieval site and especially in Crusader buildings of its town and the walls of its castle. During the Late Byzantine period, primary glass production remains were also documented as having been used as fertiliser in the agricultural plots surrounding the site, where they were found in refuse disposals together with discarded pottery, fragments of glass vessels, animal bones and other finds (Tal, 2020, p.35).

This phenomenon of an overabundance of primary glass production remains across the site and its immediate periphery is a unique spectacle when compared to other Levantine sites (Fig. 1a-d). Glass production sites such as Jalame and Beit Eliezer show an optimal use of the raw glass produced , as relatively small amounts of glass chunks have been found at these sites and the floors of their glass making furnaces have been left with almost no glass remains (Gorin-Rosen, 2000, p.54; 2002, pp.12*-13*). This phenomenon led us to check the reasons behind the site’s inadequate waste management when it came to maximising the profit from its primary glass production.

We are thus left with a research question: why were these raw glass chunks left on site? Were they considered of inferior or contaminated quality, not up to par with the known quality of Apollonia (“Levantine I”; Freestone, 2020, p.345) glass exports?

We have decided to put this to the test with the help of a contemporary glass artist, Dafna Kaffeman, to see whether these chunks are workable and can be used to produce glass objects and vessels.

Results

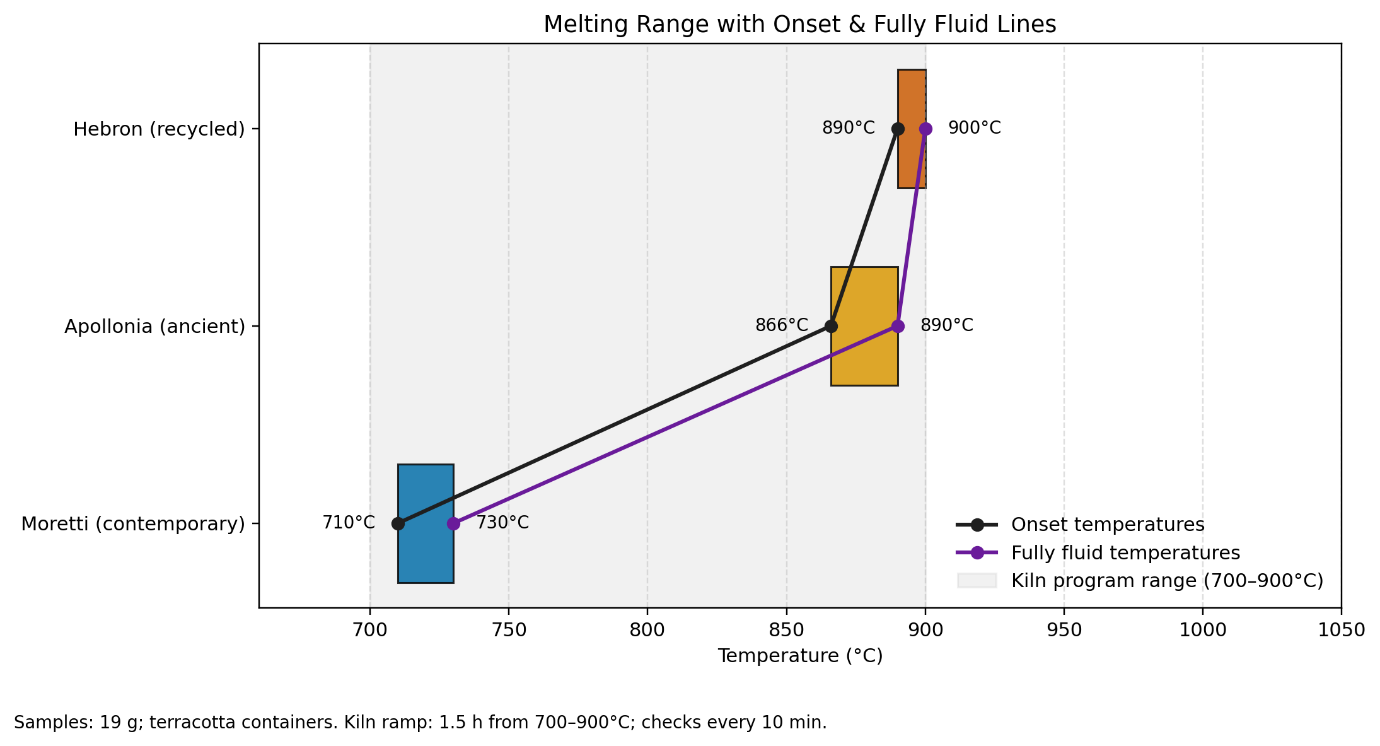

Previous attempts to remelt ancient glass, as conducted by Brill on glass from Jalame, show a melting temperature of 1,000-1,100°C in order to shape the glass (Brill, 1988, pp.278-279; Masclef, Dubois and Grevaz, 2016, p.114). More recent analytical investigations have also shown similar results (Celik, et al., 2018, p.182). During our experiment, we have tested the melting temperature of one Apollonia glass chunk as opposed to the contemporary (Moretti) four glass rods and one fragmented vessel of a local traditional (usually recycled) Hebron-made glass vessel in an electronic oven. The oven (ceramic kiln) used is of a local manufacturer ( https://har.co.il/ ). It was specially constructed for the Department of Ceramics and Glass Design at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. This kiln is intended for firing clay, porcelain, glass, and glaze works, and is notable for its ability to reach extremely high temperatures, ranging between 1,000°C and 1,320°C. It features a front-opening design with ten heating spirals installed on three side walls (with the exception of the door side), while the floor and ceiling remain free of heating elements. All glass chunks are soda-lime-silica glass, while the modern (Moretti and Hebron) consist of additional metal additives. The glass samples, each weighing 19 grams, were placed in ceramic (terracotta) containers because of their durability to high temperature, and the oven was set to a 1.5-hour rise in temperature from 700-900°C, tested every 10 minutes. We found out that the contemporary (Moretti) glass rods began to melt after one hour in the oven at 710°C, becoming consistently fluid at 730°C; the Apollonia glass chunk began to melt after two hours in the oven at 866°C, becoming fluid at 890°C, yet in a less-consistent fashion when compared to the contemporary glass. The Hebron-made glass vessel remains solid for a longer period of time, beginning to melt in 890°C, becoming totally fluid at 900°C (See Figures 2a-d, Graph 1). The Hebron glass vessel exhibits significantly higher viscosity compared to the other two types.1

It may be added that similar experiments using ancient raw glass to learn about ancient production technology were made in Israel in the mid-1990s by the artist Daniel Verbana (Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design).2 Additional experiments were made in France, using raw glass chunks from the Embiez (cf. Nenna, 2009, no. 3) and Sanguinaires (cf. Rolland, 2021, pp.41-43; Masclef, Dubois and Grevaz, 2016, p.114) shipwrecks near France.

Graph 1. Graph showing difference in melting temperature of the three glass types.

We have collected small raw glass chunks from the Apollonia-Arsuf Excavation Project, removed from refuse dumps that were assembled on-site as well as surface finds. A total of some 30 samples, ranging from 1x2, 2x4 cm in size, mostly of translucent bluish-green glass with a few samples of amber and opaque blue glass (See Figure 1d), were used in this study. The 30 samples are divided between 20 that came from dismantled furnaces remains from Area O located in the north part of the site and some additional ten chunks found scattered as surface finds throughout the site. We detected no apparent difference in the chunks in terms of their visual appearance. These samples were worked by flame working, melted and stretched as narrow rods, tooled and blown to check their quality and characteristics. The burner (Carlisle CC) produces two distinctive flames, a centre-fire (pre-mixed) and an outer fire (surface mix). Similarly, contemporary glass rods of opaque and translucent colours of soft (Moretti) glass rods and Hebron glass vessels were also manipulated, tooled and blown, in order to examine the difference in their working process. The chemical composition of the contemporary glass used by the artist was similar to the ancient glass, soda-lime-silica (Tal, Jackson-Tal and Freestone, 2004, pp.61-65). The different melting temperature was documented in the oven; however, it seems that a less intense (softer) flame was better for manipulating the ancient glass.

The artist used two types of ancient glass remains: mostly translucent and a few opaque, clear glass chunks and pieces of glass chunks attached to furnace building materials. Larger glass chunks from Apollonia were melted by the artist using outer fire, namely heating a wide and less hot flame. Focused (centre-fire) flame was used for more precise glass reworking. The annealing process was achieved by using gentle flame (a transition from a focused flame to a wide and less hot flame, with less oxygen) and vermiculite without the need of an oven. The clear glass chunks were extremely tolerant to manipulation with high plasticity, with good working quality, resistant to breakage and easy to work with a less intense (softer) flame, when compared to the contemporary glass usually used. After the cooling process, the artist did not detect any breakage on the works or bubbles, which again indicates the high quality of this ancient glass.

On the other hand, the glass chunks that had been attached to furnace building materials were extremely fragile and almost impossible to work with. Therefore, only a few pieces detached from the building materials were usable. Among these chunks, some impurities were noticed, which seem to have caused breakages throughout the working process. When working with a flame with these chunks first time, they remained whole and did not break; however, any attempt to further manipulate these worked glass chunks with the flame created a chain of breakages.

Conclusions

There is a similarity in the expansion coefficient between the ancient and contemporary glass, with higher temperatures needed for working the ancient glass than the Moretti glass, but quite similar to the Hebron glass. The clear ancient glass chunks are of high quality and easy to work with. This could be because of a very good annealing process. The pieces of glass chunks attached to furnace building materials illustrated many difficulties in their secondary reworking, and their presence on-site as primary glass production refuse is well-understood.

Therefore, we assume the reason behind the vigorous presence of high-quality raw glass chunks on site was likely due to the relatively small size of the remaining chunks. Apollonia (Sozousa) Byzantine primary glass seems to have been traded in large chunks, and it is likely that smaller chunks were considered of lesser economic value (cf. Galili, Gorin-Rosen and Rosen, 2015, noting chunks weighing 1,570 g and 546.5 g). These smaller raw glass chunks were chipped off the larger traded chunks while extracting the raw glass from furnaces at the site.

Most of the Apollonia glass chunks are bluish-green in colour. Much smaller numbers are translucent amber and green, and opaque blue glass in colour. Based on our excavations of a raw glass furnace at the site with its floor almost intact, these colours were subject to the amount of oxygen absorbed in the melting process (high level = bluish/greenish tints, and low level = amber/yellowish tints) (Tal, Jackson-Tal and Freestone, 2004, p.57). In terms of quality, the reworking of the darker coloured raw small glass chunks proved to be of a similar quality to the bluish-green glass chunks. The outcome of this research can be seen in an exhibition incorporated into the Israel Museum, Jerusalem’s permanent glass exhibition: “Dafna Kaffeman: Fragile Land.” The artworks created from ancient raw glass expand the story of local glass from ancient times to the present. They are a unique demonstration of the attempt of the artist to sketch the local landscape from a deep affinity for the past, a critical gaze on the present, and fervent hope for growth and flourishing in the future (See Figure 3).

- 1

We are indebted to Adam Salvi, Glass Workshop supervisor, Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem, for testing these samples and providing us with the results.

- 2

Verbana melted raw glass chunks from furnaces at Bet Eliezer and used them to blow glass. He was advised by Yael Israeli, Maud Spaer and Yael Gorin-Rosen. We are indebted to Yael Gorin-Rosen for bringing this unpublished information to our attention.

Keywords

Country

- Israel

Bibliography

Brill, R., 1988. Scientific Investigations of the Jalame Glass and Related Finds. In: G.D. Weinberg, ed. 1988. Excavations at Jalame: Site of a Glass Factory in Late Roman Palestine . Columbia: University of Missouri Press, pp.257-294.

Celik, S., Akyuz, T., Akyuz, S., Ozel, A.E., Kecel-Gunduz, S. & Basaranc, S., 2018. Investigations of Archaeological Glass Bracelets and Perfume Bottles Excavated in Ancient Ainos (Enez) by Multiple Analytical Techniques. Journal of Applied Spectroscopy , 85/1, pp.178-183. DOI: 10.1007/s10812-018-0629-1

Freestone, I.C., Jackson-Tal, R.E. & Tal, O., 2008. Raw Glass and the Production of Glass Vessels at Late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel. Journal of Glass Studies , 50, pp.67-80. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24191320 [Accessed January 2026]

Freestone, I.C., 2020. Apollonia Glass and Its Markets: An Analytical Perspective. In: O. Tal, Apollonia-Arsuf: Final Report of the Excavations, Volume II: Excavations Outside the Medieval Town Walls. Tel Aviv University, Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 38. University Park and Tel Aviv: Eisenbrauns and Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, pp.341-348.

Galili, E., Gorin-Rosen, Y. & Rosen, B., 2015. Mediterranean Coasts, Cargoes of Raw Glass. Ḥadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel , 115. https://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=24846&mag_id=122 [Accessed January 2026]

Gorin-Rosen, Y., 2000. The Ancient Glass Industry in Isreal: Summary of The Finds and New Discoveries. In: M.-D. Nenna, ed. La Route du verre. Ateliers primaires et secondaires du second millénaire av. J.-C. au Moyen Âge . Colloque organisé en 1989 par l’Association française pour l’Archéologie du Verre (AFAV). Lyon: Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux, pp.49-63.

Gorin-Rosen, Y., 2002. The Ancient Glass Industry in Eretz-Isreal – A Brief Summary. Michmanin , 16, pp.7*-18*

Masclef, G., Dubois, F. & Grevaz, C., 2016. Archéologie expérimentale: restitution de fours de verriers gallo-romains. Bulletin de l’Association française pour l’Archéologie du verre (AFAV) , 2016, pp.112-115.

Nenna, M.-D., 2009. Verres de l’antiquité gréco-romaine: trois ans de publication (2005-2007). Revue archéologique , 48/2, pp.283-336. https://doi.org/10.3917/arch.092.0283

Rolland, J., 2021. Le verre de l’Europe celtique, approches archéométriques, technologiques et sociales d’un artisanat du prestige au second âge du Fer . Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Tal, O., Jackson-Tal, R.E. & Freestone, I.C., 2004. New Evidence of the Production of Raw Glass at Late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel. Journal of Glass Studies , 46, pp.51-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24190930 [Accessed January 2026]

Tal, O., 2020. Apollonia-Arsuf: Final Report of the Excavations, Volume II: Excavations Outside the Medieval Town Walls . Tel Aviv University, Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 38. University Park and Tel Aviv: Eisenbrauns and Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.

Torben, S., & Kock, J., 2001. Traditional Raw Glass Pro-duction in Northern India: The Final Stage of an Ancient Technology. Journal of Glass Studies , 43, pp.155-169. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24190905 [Accessed January 2026]