The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Getting a Handle on Technological Complexity in the Acheulean: Hand-axes Make Excellent High-Energy Hafted Woodworking Tools

Reconstructing human behavioural complexity from stone tools is a primary concern for the Palaeolithic archaeologist. Two nested challenges exist in this reconstruction. Firstly, inferring the technical processes and bodies of knowledge, which combine with tools to make ‘technology’. Secondly, human technology is uniquely combinatorial, with stone tools possibly part of a more complex tool. The organic elements of such a tool, such as handles and bindings are, however, not preserved. The emergence of combinatorial technology is poorly understood, with a focus on stone points as armatures, characteristic of post-Acheulean periods leading to limited consideration of it within the Acheulean. Using experimental archaeology, here we demonstrate that hafted Acheulean type hand-axes make excellent high-energy woodworking tools. Many features of refined Acheulean hand-axes, including symmetry and thinness, aid in hafting. Having a sharp perimeter all around the tool aids in socket axe production and does not affect hafting with bindings in an adze type arrangement. These experiments raise the possibility of combinatorial technology in the Acheulean (1.7 to 0.2 ma), highlighting the potential hidden technological complexity, which a simple Acheulean hand-axe may represent.

Introduction

The research presented here shows that one of the most studied artefacts in archaeology, the Acheulean hand-axe, may not have always been used as a ‘hand’ axe, and that it functions as an excellent high-energy woodworking tool when hafted. This raises important questions about how we reconstruct behaviour and extrapolate ‘behavioural complexity’ from the archaeological record and shows that experimental archaeology has a key role to play in this.

The Acheulean hand-axe in context

The Acheulean is a spatiotemporally widespread early human techno-culture spanning Africa, Europe and parts of Asia, emerging around 1.7 Ma in Africa (Beyene, et al., 2013; Diez-Martin, et al., 2015) with its gradual replacement beginning around 0.5 Ma and late occurrences at approximately 0.2 Ma (de la Torre, et al., 2014).

Along with the continuation of simple flake technology from the preceding Oldowan period, the Acheulean is recognised by the inclusion of bifacially manufactured stone tools, such as hand-axes, cleavers, and picks (Gowlett, 2006). Of these tools, the hand-axe (See Figure 1) is the most common retouched tool and is broadly considered an archaeological index of the Acheulean.

Rather than a static technological period it is marked by gradual change in terms of hand-axes becoming more refined through increasingly intensified knapping and the use of soft organic hammers to remove thin invasive flakes (Beyene, et al., 2013: McNabb and Cole, 2015).

Theoretical background

Archaeologists are commonly left with only the tools with which to construct the behavioural complexity of the past (e.g. Torrence, 1989). These artefacts, which archaeologists recover, both represent a past technological adaptation, and like technology today, as being imbued with and representing the cultural values and adaptation of past humans (Pfaffenberger, 1992; Wenger, 2002; Ingold, 2022). Within evolutionary terms, this cultural adaptation is often scrutinised for changes in behavioural complexity (e.g. Mesoudi, et al., 2004; Birch and Heyes, 2021).

It has long been recognised that to reconstruct human behaviour, and behavioural complexity, from the material remains (i.e., archaeology), we must deconstruct the assumptions which underlie the above process (Clarke, 1973; Hodder, 1985; 1987). The archaeologists must build reliable frames of reference that allow us to move from the unanimated artefact to the ‘all singing and dancing’ behavioural complexity which we seek to reconstruct (Binford, 1977).

A central challenge, present at the first inferential step, is how much ‘technology’ remains in the archaeological tool? This challenge exists because ‘technology’ is a complicated thing, which consists of more than just tools (Sinclair, 1990; Ingold, 2022). Technology is best understood as three possible interacting elements: 1, the ‘tools’ which we can recover from excavation. 2, processes; using tools to achieve a desired outcome. 3, a body of knowledge, which relates to how the tools are made, used, repaired, discarded, and potentially recycled (Arthur, 2009; Barham, 2013). For the more theoretically leaning, this body of knowledge might be seen as the learning requirements, savoir faire and connaissance, of a socially mediated chaîne opératoire (Edmonds, 1990). Reconstructing the final two elements of technology represents the greatest challenge, and as shown in this research, the value of experimental archaeology.

A further challenge permeates many of the above inferential steps due to preservation bias and the nature of human technology. The preservation of organics is exceptionally rare in Palaeolithic and Stone Age contexts (Thieme, 1997; Goren-Inbar, et al., 2002; Aranguren, et al., 2018; Taylor, 2018; Barham, et al., 2023), with the overwhelming majority of archaeology from these periods being stone tools. Human technology is, however, uniquely defined by its inclusion of artefacts manufactured from multiple complimentary materials; it is combinatorial (Barham, 2013). Throughout the later periods of the human past, these stone tools will have been combined with organic materials, like wood, bone, or antler handles, resins and glues, bindings made from animal hide or twisted plant materials, to make combinatorial tools (Ibid.). The stone tools are analogous to the blade of a Stanley knife, a blade in pencil sharpener, a surgical scalpel blade or, perhaps, a blade in a futuristic 30 blade shaving apparatus, guaranteed to maximise the efficiency of beard removal. With only the blade, or stone tool, reconstructing the ‘technology’ en route to bigger concepts of behavioural complexity requires the careful construction of frames of reference.

While there is much to be said for contextual archaeological approaches (Hodder, 1987; Barrett, 1987) and ethnoarchaeology (Gould, 1978; cf. Wobst, 1978), experimental archaeology is rooted in constructing the frames of reference needed to move from simple unanimated artefacts to the associated processes and bodies of knowledge needed to reconstruct a fuller understanding of past ‘technology’ (Ascher, 1961; Mathieu, 2002).

As combinatorial technology is a human derived trait, meaning it emerged in our lineage (Barham, 2013), we have an additional challenge of knowing when to treat stone tools as the whole artefact, and when to treat them as part of a larger composite tool. Despite the significance of combinatorial technology in human evolution, limited dedicated research has been performed for its identification (Rots, 2002; 2003; 2010; 2015). Both earliest claims for hafting relate to hafted armatures, (Wilkins, et al., 2012; Sahle, et al.., 2013) with both studies also challenged (Rots and Plisson, 2014; Douze, et al., 2018) and subsequently defended (Wilkins, et al., 2015; Sahle and Braun, 2018).

The limited research, with a focus on points, which appear as a more regular archaeological feature after the Acheulean (Clark, 1988; Will and Scerri, 2024) combined with experimental studies showing Acheulean hand-axes do indeed function in the hand (Jones, 1980; Mitchell, 1995; Machin, et al., 2007), have led to almost no consideration that hand-axes might have been hafted as part of a combinatorial tool (Cf. Lambert-Law, 2015). Using an experimental archaeological approach, here we show that Acheulean hand-axes function as excellent high-energy woodworking tools when hafted. We do not suggest that all Acheulean hand-axes were used hafted but raise the possibility that from their 1.6-million-year chronology and multi-continental spatial distribution, that some may have been.

Methods

Tool construction

Two main tool forms were manufactured to demonstrate the functionality of Acheulean hand-axes as high-energy hafted tools: adzes, and socket axes. Socket axes are the simpler design involving just a lithic inserted into a wooden handle. Adzes involved the use of a rawhide binding to attach the lithic to the handle.

The clefted, split axe arrangement, with the handle fully split and the haft closed around the lithic using bindings, was also tested. Despite several designs and materials tested, this design proved unsuitable for high-energy percussive actions, with hafts failing almost instantly.

The research presented here refers to seventeen replica flint hand-axes directly hafted in a juxtaposed arrangement as adzes, and twenty replica flint hand-axes used in an axe type arrangement with the lithics directly inserted into a carved hole made in the handle.

Lithic hand-axe manufacture

Generally fine-grained flint from Caistor Quarry, Caistor St Edmunds, UK, was knapped by the authors (CS and KL), using both hard hammer (various quartzite) and soft hammer (red deer, Cervus elaphus , antler) techniques, using both flakes (debitage) and complete nodules (façonnage) to produce hand-axes deemed ‘Acheulean’ by Prof. Gowlett, a renowned expert in the Acheulean (Gowlett, 1978; 2006; 2021). The use of soft hammer reduction allows thin invasive flakes to be removed. This permits material to be removed from the centre of the tool without removing too much edge and results in the thinner hand-axes characteristic of the later periods of the Acheulean (Beyen, et al., 2013).

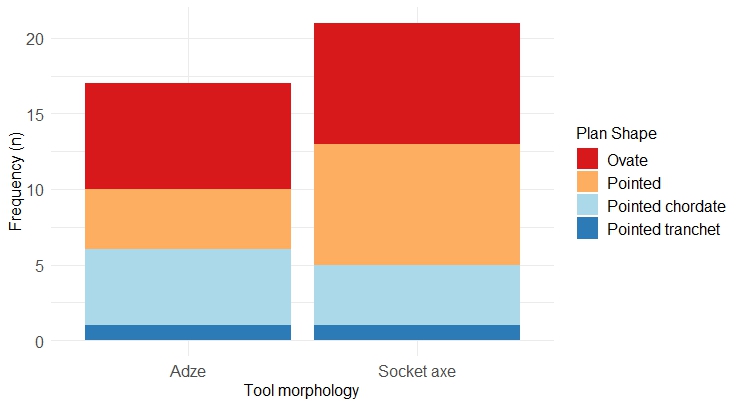

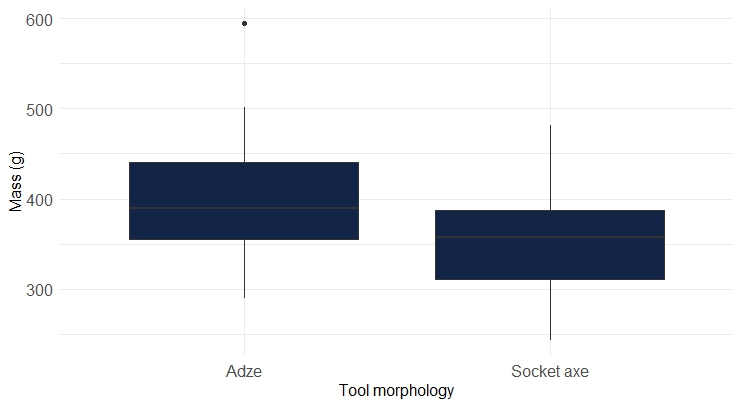

Following Roe (1969) with the addition of chordate (tear drop) and tranchet, which refers to the specific final flake removal which truncates the tool (Garcia-Medrano, et al., 2019), the plan tool morphologies for adzes and socket axes are shown in Graph 1, with a comparison of hand-axe mass shown in Graph 2.

Graph 1. Tool morphologies for adzes and socket axes.

Graph 2. Mass of hand-axes used for adzes and socket axes.

Handle construction

Several wooden handles were manufactured and tested to explore variability in performance. The wooden handles were manufactured with modern steel tools for rapidity and more familiarity ensuring a well-fitting haft that would be more representative of that which an expert stone tool user could achieve.

Juxtaposed hafts used for adzes

- JXTA and JXTB were made from an African wood Albizia antunesiana , with JXTA having no backstep. These were designed and made by John Kanyatta (JK), a Zambian expert (See Figure 2). Mukese wood was selected by JK as local wood still used for making percussive axe and adze handles. It was included in this research to explore materials across the main African range of the Acheulean.

- JXTC was made from ash ( Fraxinus sp. ) due to its shock-resistant properties. It initially had a step, which was later broken off during use from lithic pressure. This was manufactured by Will Adams, a UK Bushcraft expert. Function of the handle improved with the step removal as the lithic did not rotate against which increased the pressure on the bindings (See Figure 3).

- JXTE was made by the author (CS) from sycamore ( Acer pseudoplantanus ) and included a step and a slightly bowled platform to increase haft articulation (See Figure 4).

Inserted hafts used for socket axes (See Figure 5)

- AXE1 was made from alder ( Alnus glutinosa ) by Phill Gregson (PG), a master wheelwright. It partially split during use but was repaired with rawhide bindings, becoming AXE1.2, and then

- AXE1.3 with a purposely split and opened haft for better lithic embedding.

- AXE 2 was made from cherry wood ( Prunus avium ) by CS, featuring a knot at the top of the handle and rawhide to prevent splitting.

Binding construction

Rawhide bindings were manufactured from an untreated cow and red deer hide by CS. The hide had both the flesh and hair scraped off with steel tools and stone tools, with the use of an alkaline solution used to aid in hair removal. The hides were subsequently cleaned with a pressure washer (on low) to remove the alkaline (See Figure 6) Steel tools were again supplemented for stone tools for consistency and more familiarity with steel tools. There was no perceptible difference in the areas of hide worked with stone and steel tools.

While we used commercially available sodium hydroxide 0.5 molar (NaOH) for this experiment, the same process was achieved in exploratory experiments using fresh wood ash as a lye solution. Commercially available rawhide, sinew, and artificial sinew were tested but proved insufficient, failing quickly with high-energy use. These commercial materials were not used further in the experiments.

No adhesives or fillers were employed in these experiments. This decision was based on the lack of archaeological evidence for adhesive manufacture in the Acheulean and to demonstrate that even a simple design provides a highly functional tool.

Tool Articulation

Juxtaposed hafting- adzes

Lithics were directly hafted onto adze handles without wrapping (See Figure 7). Some exploratory experiments showed that wrapping the tool before hafting reduced the haft strength. Wet rawhide bindings were applied with maximum tension and wrapped in both directions to increase stability. The bindings were allowed to fully dry on a warm radiator, or close to a fire until they were solid (See Figure 8). For each hafted adze, this produced a hafted tool with limited movement between the lithic and the handle. Forcing the bindings to dry too quickly led to them becoming weak and brittle, which led to haft failure. De-hafting was achieved by re-soaking the bindings until they became soft and pliable.

Inserted hafting - socket axes

For socket axes, hand-axes were directly inserted into wooden handles often with the butt of the tool as the working edge (See Figure 9). Socket axe 4 demonstrated that a tip working edge was possible with broader tranchet tips. The force of action seated the lithic into the handle. A sharp strike on the handle above the lithic was used to de-haft the tools.

Tool use

The hafted tools were all used in heavy duty percussive woodwork. As the experiment existed within a larger use-wear programme, the use duration varied. Most of the tool use was performed by CS in the experiment archaeology research training hub (EARTH) workshop at the University of Liverpool. Some experimentation was performed in Alder Car woodland, Silsden, North Yorkshire, UK. This included the felling of a large, approximately 45 cm diameter dead standing sycamore tree, performed by various members of West Yorkshire Bushcraft, who have permissive access to the private woodland. In a separate experiment, CS felled and sectioned into 4 an approximately 10 cm diameter live rowan tree ( Sorbus aucupairia), taking approximately 12 minutes (See Figure 10). Full details of the tools used can be found in Table 1, Appendix 1.

Results and discussion

The key findings are that even though the replica Acheulean hand-axes had been thinned, in some cases aggressively, they were able to withstand high-energy percussive work without failing. In some cases, the working edge was damaged during use, which was easily repaired by retouch while still hafted.

It is also interesting that certain design features of Acheulean hand-axes suited hafting. A key feature which aided hafting in the socket arrangement, was having a sharp perimeter. This caused the hand-axe to bite into the handle and resulted in a secure haft. For adzes, with the bindings in contact with a sharp edge, this was expected to cause problems. While this was the case for the commercial rawhide tested, when using the rawhide that we manufactured there was no issue, with both the rawhide and the haft surviving heavy use. Indeed, the same bindings were used in several experiments as they were not damaged. The argument that we would observe archaeological examples of hand-axes with their edges ground off to protect the bindings, had they been used hafted, is refuted by these findings. In socket axes, having sharp unmodified edges is functional in producing a more secure haft. Modifying and blunting the edges of adzes by grinding them is an unnecessary production step as the sharp edges are not capable of cutting the bindings that secure the lithic to the handle.

Tools which were well thinned were also much easier to haft. In socket axes, thinner tools acted less like a wedge in splitting the handle. In adzes, the thinner tools had a flatter profile across the face, which again, made hafting much easier as it aided articulation to the haft. In both adzes and socket axes, symmetry was also significant. Hand-axes which exhibited significant asymmetry, either in plan or in any other volumetric measure, were either harder to haft, or simply unable to be hafted. Conversely, the more symmetrical, the easier the tool was to haft, and the better it performed, with reduced twisting and increased balance in the haft.

Although not reported here, the use-wear which formed, or indeed did not form on the working edge, did not produce an obvious pattern, such as large scarring, or significant polish, which would have been ‘observed by now’ if present in the archaeological record. In all cases, there was no well-developed polish. Microfractures did occur, although these proved hard to distinguish from the retouch. Such curated tools would also have been well repaired, potentially removing any use-wear which would easily identify the tools as having been used in high-energy percussion.

The most significant contribution of these experiments is to highlight the potential hidden complexity of archaeological stone tools when they are taken at face value. The difference in complexity between a simple hand-held Acheulean hand-axe, and one that was hafted was remarkable. Despite being able to make Acheulean hand-axes of a ‘passable nature’, CS initially struggled to make completed hafted tools, requiring significant input from KL, and other experts mentioned in the paper. Bindings and handles may both have a chaîne opératoire , that may be more complex than the production of the hand-axe. In both cases they require a mix of organic and nonorganic tools, as well as significant planning and time requirements. It is also likely that such an adze used in natural settings might require some form of waterproofing, to prevent the bindings becoming wet, leading to haft failure. These hidden bodies of knowledge, and level of behavioural complexity, are not even being considered if we assume a lack of hafting.

Of course, the experiments here, much like a lot of experimental archaeology, demonstrate a possibility; they allow for a hypothesis to be constructed (Eren and Meltzer, 2024). The good news in this case is that through a developed functional use-wear analysis program, detecting hafting on such tools should be possible (Rots, 2010). Such an approach would allow us to ‘get a handle’ on the technological and behavioural complexity of ancestral hominins.

Funding and/or Competing interests

Financial support was received from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, North West Consortium Doctoral Training Partnership as a PhD stipend for CS.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Keywords

Appendix 1

| Tool name | Prehensile mode | Haft ID | Action | Contact material | Time (mins) | Plan shape | Mass (g) |

| Adzes | |||||||

| Adze 3 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 20 | Pointed | 444 |

| Adze 4 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 20 | Pointed tranchet | 368 |

| Adze 5 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 30 | Ovate | 458 |

| Adze 6 | Hafted Adze | JXTA | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 30 | Ovate | 396 |

| Adze 7 | Hafted Adze | JXTA | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 30 | Pointed | 467 |

| Adze 8 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 30 | Pointed chordate | 536 |

| Adze 9 | Hafted Adze | JXTA | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 38 | Ovate | 400 |

| Adze 10 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 40 | Ovate | 398 |

| Adze 11 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 50 | Pointed chordate | 288 |

| Adze 12 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 60 | Pointed | 398 |

| Adze 13 | Hafted Adze | JXTA | Adzing and dig | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 60 | Pointed chordate | 590 |

| Adze 14 | Hafted Adze | JXTC | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 60 | Pointed chordate | 344 |

| Adze 15 | Hafted Adze | JXTB | Adzing | Fresh soft wood (Birch) | 60 | Ovate | 338 |

| Adze 16 | Hafted Adze | JXTB | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 90 | Pointed chordate | 400 |

| Adze 17 | Hafted Adze | JXT C | Adzing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 90 | Pointed | 595 |

| Socket Axes | |||||||

| Socket Axe 3 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Dry hard wood (small Cherry sections) | 15 | Pointed chordate | 257 |

| Socket Axe 4 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.3 | Tip (R) | 15 | Pointed tranchet | 381 | CS |

| Socket Axe 5 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Fresh soft wood (Birch) | 20 | Pointed | 337 |

| Socket Axe 6 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Wood mix | 20 | Pointed | 290 |

| Socket Axe 7 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1 | Axing | Dry hard wood (Ash) | 30 | Pointed | 245 |

| Socket Axe 8 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.3 | Butt | 40 | Ovate | 381 | CS |

| Socket Axe 9 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 2 | Axing | Fresh hard wood (Ash) | 42 | Ovate | 465 |

| Socket Axe 10 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1 | Axing | Dry hard wood (Yew and Ash) | 45 | Pointed | 482 |

| Socket Axe 11 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Hard dry wood (Ash) | 50 | Pointed | 362 |

| Socket Axe 12 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1 | Axing | Fresh hard wood (Ash) | 60 | Ovate | 352 |

| Socket Axe 13 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1 | Axing | Dry hard wood (Ash) | 60 | Ovate | 446 |

| Socket Axe 14 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1 | Axing | Fresh hard wood (Ash) | 15 | Ovate | 305 |

| Socket Axe 15 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1 | Axing | Dry hard wood (Ash) | 60 | Ovate | 345 |

| Socket Axe 16 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Dry hard wood (Ash round) | 90 | Pointed chordate | 394 |

| Socket Axe 17 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Fresh soft wood (Birch) | 90 | Ovate | 268 |

| Socket Axe 18 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Fresh soft wood (Birch) | 90 | Ovate | 452 |

| Socket Axe 19 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Fresh soft wood (Birch) | 90 | Ovate tranchet | 426 |

| Socket Axe 20 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Fresh soft wood (Birch) | 90 | Pointed chordate | 430 |

| Socket Axe 21 | Hafted Socket Axe | Axe 1.2 | Axing | Fresh soft wood (Birch) | 90 | Ovate | 243 |

Table 1. Tools used in experiment.

Bibliography

Aranguren, B., Revedin, A., Amico, N., Cavulli, F., Giachi, G., Grimaldi, S., Macchioni, N. and Santaniello, F., 2018. Wooden tools and fire technology in the early Neanderthal site of Poggetti Vecchi (Italy). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(9), pp. 2054-2059.

Arthur, W. B., 2009. The Nature of Technology. London: Allen Lane.

Ascher, R., 1961. Experimental Archaeology. American Anthropologist, 63(4), pp. 793-816.

Barham, L., 2013. From Hand to Handle: The First Industrial Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barham, L., Duller, G. A. T., Candy, I., Scott, C., Cartwright, C. R., Peterson, J. R., Kabukcu, C., Chapot, M. S., Melia, F., Rots, V., George, N., Taipale, N., Gethin, P. and Nkombwe, P., 2023. Evidence for the earliest structural use of wood at least 476,000 years ago. Nature (London), 622(7981), pp. 107-111.

Barrett, J. C., 1987. Contextual archaeology. Antiquity, 61(233), pp. 468-473.

Beyene, Y., Katoh, S., WoldeGabriel, G., Hart, W. K., Uto, K., Sudo, M., Kondo, M., Hyodo, M., Renne, P. R., Suwa, G. and Asfaw, B., 2013. The characteristics and chronology of the earliest. Acheulean at Konso, Ethiopia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(5), pp. 1584-1591.

Binford, L. R., 1977. For theory building in archaeology: essays on faunal remains, aquatic resources, spatial analysis, and systematic modeling edited by Lewis R. Binford. Studies in archeology New York: Academic Press.

Birch, J. and Heyes, C., 2021. The cultural evolution of cultural evolution. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological sciences, 376(1828), pp. 1-9.

Clark, J. D., 1988. The Middle Stone-Age of East-Africa and the Beginnings of Regional Identity. Journal of World Prehistory, 2(3), pp. 235-305.

Clarke, D., 1973. Archaeology - Loss of Innocence. Antiquity, 47(185), pp. 6-18.

de la Torre, I., Mora, R., Arroyo, A. and Benito-Calvo, A., 2014. Acheulean technological behaviour in the Middle Pleistocene landscape of Mieso (East-Central Ethiopia). Journal of Human Evolution, 76, pp. 1-25.

Diez-Martin, F., Yustos, P. S., Uribelarrea, D., Baquedano, E., Mark, D. F., Mabulla, A., Fraile, C., Duque, J., Diaz, I., Perez-Gonzalez, A., Yravedra, J., Egeland, C. P., Organista, E. and Dominguez-Rodrigo, M., 2015. The Origin of The Acheulean: The 1.7 Million-Year-Old Site of FLK West, Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania). Scientific Reports, 5.

Douze, K., Delagnes, A., Rots, V. and Gravina, B., 2018. A reply to Sahle and Braun's reply to The pattern of emergence of a Middle Stone Age tradition at Gademotta and Kulkuletti (Ethiopia) through convergent tool and point technologies'[J. Hum. Evol. 91 (2016) 93-121]', Journal of Human Evolution, 125, pp. 207-214.

Edmonds, M., 1990. Description, Understanding and the Chaine Opératoire: Technology in the Humanities., Archaeological reviews from Cambridge, 9(1), pp. 55-70.

Eren, M. I. and Meltzer, D. J., 2024. Controls, conceits, and aiming for robust inferences in experimental archaeology. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 53(104411), pp. 1-10

Garcia-Medrano, P., Olle, A., Ashton, N. and Roberts, M. B., 2019. The Mental Template in Handaxe Manufacture: New Insights into Acheulean Lithic Technological Behavior at Boxgrove, Sussex, UK. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 26(1), pp. 396-422.

Goren-Inbar, N., Werker, N. and Feibel, C. S., 2002. The Acheulian site of Gesher Benot Ya'aqov: the wood assemblage. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Gould, R. A. and School of American, R., 1978. Explorations in ethno-archaeology edited by Richard A. Gould. School of American Research. Advanced seminar series. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Gowlett, J. A. J., 1978. (B) Kilombe—an Acheulian site complex in Kenya. Geological Society, London, Special Publication., 6(1), pp. 337-360.

Gowlett, J. A., 2006. The elements of design form in Acheulian bifaces: modes, modalities, rules and language. In N. Goren-Inbar and G. Sharon, eds. Axe Age: Acheulian tool-making from quarry to discard . London: Equinox, pp. 203-221.

Gowlett, J. A. J., 2021. Deep structure in the Acheulean adaptation: technology, sociality and aesthetic emergence., Adaptive Behavior, 29(2), pp. 197-216.

Hodder, I., 1985. Postprocessual Archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, 8, pp. 1-26.

Hodder, I., 1987. The archaeology of contextual meanings. New directions in archaeology Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ingold, T., 2022. “Society, nature and the concept of technology,” in The Perception of the Environment . 1st ed. Routledge, pp. 392–405.

Jones, P. R., 1980. Experimental Butchery with Modern Stone Tools and Its Relevance for Palaeolithic Archaeology. World Archaeology, 12(2), pp. 153-165.

Lambert-Law, T. S., 2015. An exploration of use-wear analysis Acheulean large cutting tools: The Cave of Hearths' bed 3 assemblage. Masters of Science in Archaeology. University of Witwatersrand.

Machin, A. J., Hosfield, R. T. and Mithen, S. J., 2007. Why are some handaxes symmetrical? Testing the influence of handaxe morphology on butchery effectiveness., Journal of Archaeological Science, 34(6), pp. 883-893.

Mathieu, J., 2002. Experimental archaeology: replicating past objects, behaviours, and processes / edited by James R. Mathieu. BAR. 1035 Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

McNabb, J. and Cole, J., 2015. The mirror cracked: Symmetry and refinement in the Acheulean handaxe. Journal of Archaeological Science-Reports, 3, pp. 100-111.

Mesoudi, A., Whiten, A. and Laland, K. N., 2004. Perspective: Is human cultural evolution Darwinian? Evidence reviewed from the perspective of The Origin of Species. Evolution, 58(1), pp. 1-11.

Mitchell, J. C., 1995. Studying Biface Utilisation at Boxgrove: Roe Deer Butchery with Replica Handaxes. Lithics, 16, pp. 64 - 70.

Pfaffenberger, B., 1992. Social-Anthropology of Technology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 21, pp. 491-516.

Roe, D. A., 1969. British Lower and Middle Palaeolithic Handaxe Groups. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 34, pp. 1-82.

Rots, V., 2002. Bright spots and the question of hafting. Anthopologica et Praehistorica, 113, pp. 61-71.

Rots, V., 2003. Towards an understanding of hafting: the macro- and microscopic evidence Antiquity, 77(298), pp. 805-815.

Rots, V., 2010. Prehension and Hafting Traces on Flint Tools, a Methodology. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Rots, V., 2015. Keys to the Identification of Prehension and Hafting Traces. In J.M. Marreiros, J.F. Gibaja Bao and N.F. Bicho, eds. Use-Wear and Residue Analysis in Archaeology . London: Springer, pp. 83-104.

Rots, V. and Plisson, H., 2014. Projectiles and the abuse of the use-wear method in a search for impact. Journal of Archaeological Science, 48, pp. 154-165.

Sahle, Y. and Braun, D. R., 2018. A reply to Douze and Delagnes's 'The pattern of emergence of a Middle Stone Age tradition at Gademotta and Kulkuletti (Ethiopia) through convergent tool and point technologies. [J. Hum. Evol. 91 (2016) 93-121] Journal of Human Evolution, 125, pp. 201-206.

Sahle, Y., Hutchings, W. K., Braun, D. R., Sealy, J. C., Morgan, L. E., Negash, A. and Atnafu, B., 2013. Earliest Stone-Tipped Projectiles from the Ethiopian Rift Date to > 279,000 Years Ago. Plos One, 8(11).

Sinclair, A., 1990. Technology as Phenotype? An Extended Look at Time, Energy and Stone Tools: Technology in the Humanities Archaeological reviews from Cambridge, 9(1), pp. 71-81.

Taylor, M., Bamforth, M., Robson, H. K., Watson, C., Little, A., Pomstra, D., Milner, N., Carty, J. C., Colonese, A. C., Lucquin, A. and Allen, S., 2018. The Wooden Artefacts, In N. Milner, C. Conneller and B. Taylor, eds. Star Carr Volume 2: Studies in Technology, Subsistence and Environment. York: White Rose University Press, pp. 367 - 418.

Thieme, H., 1997. Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany. Nature 385, pp. 807-810.

Torrence, R., 1989. TIME, ENERGY AND STONE TOOLS. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., 2002. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Learning in Doing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilkins, J., Schoville, B. J., Brown, K. S. and Chazan, M., 2012. Evidence for Early Hafted Hunting Technology. Science, 338(6109), pp. 942-946.

Wilkins, J., Schoville, B. J., Brown, K. S. and Chazan, M., 2015. Kathu Pan 1 points and the assemblage-scale, probabilistic approach: a response to Rots and Plisson, "Projectiles and the abuse of the use-wear method in a search for impact". Journal of Archaeological Science, 54, pp. 294-299.

Will, M. and Scerri, E., 2024. The generic Middle Stone Age: fact or fiction?. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 59(1), pp. 4-21.

Wobst, H. M., 1978. The Archaeo-Ethnology of Hunter-Gatherers or the Tyranny of the Ethnographic Record in Archaeology. American Antiquity, 43(2), pp. 303-309.